Vienna, 1980-1989

I had zero desire to see or travel through the Middle East, so I flew out of Bombay, landed in Germany, and hitchhiked into Vienna. I came close to staying forever.

Vienna is one of the finest spots on the planet, at least to me. There are quite a few people that hate it, instantly, upon arrival. And then there are those who grew up there, some of whom hate it with more of a long-term, slow-boiling loathing. I, however, loved it. Whatever spell it exerts worked on me. The Viennese that I met and dealt with were honest, kind, cultivated and peaceful. Their society is a place of safe streets, a deep appreciation of the arts, a love of nature and a strong sense of history.

Vienna was once the head of an empire of 52 million people and an almost uncountable number of languages, and it lasted from 1282 to 1918. The empire had established itself more through deals and cunning marraiges than martial ferocity, and it was not known for being over-repressive. “Krieg lass andere-fuhren, du, gluckliches Osterreich Heirat!” “Others can fight wars, you, lucky Austria get married.” A better-known translation goes “Felix Austria,” which means Happy, and I knew a singer in Vienna who gave himself that name.

It could be said that the Austrian Empire was an attractive sort of overlord, being stylish and cultivated and competent, but without the attendant marching around or sword-sharpening that characterized the Prussians. Elegance was probably the word that came to mind most often, and there is a lot of it remains, even today. The balls that are held, themed and not, and are as common as sporting events in Texas.

And the balls, along with so many other things in life, needed music. Musicians were born and raised there, other musicians were drawn to the place, from Beethoven to Joe Zawunil, from Shubert to Falco. The writer Stephen Zweig, one of the city’s most famous sons, once wrote “It was the peculiar genius of Vienna, the city of music, to resolve all these contrasts harmoniously in something new and unique…in hardly any other European city was the urge towards culture as passionate as in Vienna.”

Of course, I was there in the 1980s. Had I lived there in the 1930s and 40s my take would have been quite different. The Austrians—and that included a lot of Viennese—welcomed Hitler’s anschluss with the kind of ecstasy usually associated with the arrival of John, Paul, George and Ringo. They tripped over one another to force Jews to scrub anti-Nazi graffiti of the sidewalks. With toothbrushes. William Shirer, CBS journalist and author of The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, wrote that the Austrians were doling out manners of degradation that he hadn’t seen even in Germany.

So, I think the city provides a fine illustration of the parallel good/evil urges of the human race. Sometimes it’s all rolled up into one guy. For instance, the man who brought order to the streetcars and created the basis for the city’s dreamlike public transport system was Mayor (Handsome) Karl Lueger, who was burgomeister from 1897 – 1910. He also vastly improved the water, gas and electricity supply, the parks, the gardens and the social justice systems.

It is an amazing record, and at first blush he was an early Fiorello La Guardia. However, any politician that wanted to get anywhere in politics of the time had to come to grips with the untamed, vicious anti-Semitism that passed for a creed in the Central European working and shopkeeper classes. The workers thought they were being exploited, and of course they were, by big-money capitalists, but it was less complicated for them to imagine their exploiters as being Jewish. People love the chance to see things in terms of black and white, something that has had some dreadful consequences in my own country . The small shopkeepers felt pressured by big department stores, which they felt were a Jewish—not a capitalist—invention. Plus, the shopkeepers were almost all Catholics, a religion not noted for its tolerance of competition. These folk—the little guys–hated the Jews with a pure fire that would burn all the way to Bergen-Belsen.

Dr. Lueger, apparently, didn’t really care much about Jews one way or the other, but he knew a winning political stance when he saw it, and he jumped right in. He billed himself as a friend of the little guy, the people’s pal. Very much like Trump, he normalized fringe whackos and dazzled the electorate with pithy little one-liners, referring to the capital of Hungary as “Judapest” and expressing the hope that all the Jews in the city would be taken on an ocean liner and scuttled in the middle of the Atlantic.

He was elected, riding under the Jew-baiting banner of convenience, but then he proceeded to toss all that aside and just do what a mayor is supposed to do, fix and improve things. He wasn’t the first—and certainly not the last—politician to shrug and mutter, “Boy, the things you gotta do to get elected.”

Stefan Zweig, who was Jewish and lived in that time and place, wrote about Handsome Karl, and was always quick to point out that not a single one of the mayor’s anti-Semitic ideas or rants were ever actually put into law.

The Jews of Vienna suffered not at all from Handsome Karl’s electioneering antics, but their children were less lucky. One of his greatest admirers was a young vagrant, who was, at that time, living in a homeless shelter and carrying bags at the Westbahnhof (West side train station) for tips. He followed Dr. Lueger’s career closely, and brought many of the older man’s tricks into his own repertoire. His name, of course, was Adolph Hitler.

Book Hint: The World of Yesterday

Stefan Zweig delivered quite a diverse body of work; the libretto for an opera by Richard Strauss, a bio of Marie Antoinette, and Letter From an Unknown Woman, which was made into a beautiful film by Max Ophuls.* But he’s best known for The World of Yesterday, a stunning history of his homeland from around 1900, the time of Emperor Franz Joseph, up until WWII. He wrote of the many people he met and wrote about up until the late 1930s. After Austria became part of the Third Reich, he was lucky enough to get to England and finally Brazil. Once safe, however, upon turning 60, he (and his girlfriend) committed suicide. He felt that “Europe is destroying itself,” he he couldn’t bear it.

This manner of exit is another aspect of the Middle European character, where people often analyze things to death. Sometimes this includes themselves. True to his roots, Zweig, along with his girlfriend, drank poisoned wine.

*Father of Marcel Ophuls, director of The Sorrow and the Pity and Memory of Justice.

Well, the Vienna I entered was, at this point, really another world of yesterday. Austria had a democratic socialist government. Bruno Kreisky, a non-practicing Jew, was the extremely popular chancellor, tolerance was the byword, and the place was jumping. There were music venues all over the place, from tiny clubs to ballrooms. American music, all forms of it, from heavy metal to jazz, was leading the pack. American musicians were held in something close to respect, which we all found a bit confusing. Accustomed to being treated with disdain, suspicion and outright contempt in the United States, we kept waiting for the natural order to reassert itself and send us all back to loading trucks. But it never happened. It took years, but I eventually became pretty good at forming bands, rearranging cover songs, and even hustling up gigs.

As I mentioned above, there’s hardly any street crime, and women walking home alone, unmolested, at 3:00 am was and is a common sight. The streets are so safe that expensive, portable goods were displayed in lighted store windows, all day and all night. This included Glock-9s, which are in fact an Austrian product. I repeat, gun shops would leave their side arms out all night, protected by nothing more than some glass and an obedient populace. Can you imagine an American gun shop with overnight window displays??

So, to me, this was a tremendous, civilized lifestyle, and I was glad to discover it. I also discovered that I was more of a bandleader than a sideman. I also started writing entire songs, rather than just the lyrics.

THE VIENNA COFFEEHOUSE DIGRESSION

One of the greatest attractions Vienna had, for me, anyway, was its coffeehouses. They were, although partially subsidized by the government, still functioning successfully. They represented a tradition that even the free market conservatives agreed should be maintained.

The ruling burghers—from the left or the right—have a reputation for inflexible conservatism, but it manifests itself most often as an inflexible conservationism, especially towards things like natural resources and mom & pop stores and classically decorated coffeehouses. Despite what we think of as certain immutable laws of capitalism, it works, somehow. For several years I lived in a neighborhood of small, independent shops that had been in the same family for heaven knows how many generations. One was a tailor’s, another sold umbrellas and rain gear, one sold bonbons, another dealt in tobacco and its byproducts, yet another flogged cheese and sausages. I have only one idea how they stayed in competition with the chain and department stores: the government’s rule that almost every business had to close between noon and 1:00 or 2:00 pm. This was designed to help mom & pop get a rest without losing business to the big playahs.

I loved the coffeehouses, of course, and I’ve spent the rest of my life, looking in every country I’ve been to, for their equivalent.

Vienna, the pedestrian intersection of Graben and Kartnerstrasse.

Vienna, winter 1986. I’m standing on Naglergasse

The Cafe Central, old city, Vienna

I wrote a book about coffeehouses while sitting in coffeehouses, although, true to my code, I never tried to flog it. I favored the Café Sperl, in the 5th District, which put it close to the outdoor food market called the Naschmarkt.

The Sperl, which is still in business, is an old, well-preserved place. The appointments are nicely polished wood, the table tops are marble and the light comes from elaborate, brilliantly buffed chandeliers. The waiters wear tuxedos, which means that this is one of the better places. A café waiter in Vienna is not permitted to wear a tuxedo until he has finished an 18-month course in café waitership. This course covers the proper methods of walking softly, remembering titles that go with faces, keeping track of 15 concurrent orders, identifying big spenders and ejecting drunks without raising one’s voice.

On this day, most of the other customers were either writing, reading, speaking softly or posing. It was also possible to play chess or cards or billiards, and all the materials were provided by the management. There was a rack of newspapers and magazines, in four languages, fitted onto wooden holders to prevent people from folding them up and taking them home.

Across from me, an elderly gentleman with a professorial goatee and a deerstalker’s cap was speaking to himself in German and answering in Portugese. Three tables away sat a young woman who looked like she answered to the name of La Countessa Di Fifi Mafaldi-Grundig. She fitted a cigarette into a slim ivory holder and froze her position for two seconds. Four young men, appearing from different parts of the café, brandishing lighters, made a mad dash for her table, but the waiter beat them to it. (Another useful skill acquired at café waitership school, I guess.)

Everybody is, in the words of William Hazlitt, lord of one’s self, unencumbered by a name. Until you want the waiter to know it, anyway. It’s up to you. And it’s up to you to decide how to use this public space. You can hate coffee but simply love showing off your new suit or dress. If you can’t read, the newspapers and magazines won’t have much appeal for you, but you can meet other people there, even other illiterates, and talk and talk and talk and talk about whatever things illiterates like to talk about. Religion. Your glorious ancestors. Television. Trump…

You can play billiards or chess. You can wait in comfort for people who are late for appointments. And, although the national language is German, this happens in Vienna as frequently as it does in Miami.

Another appealing aspect of the coffee house is that it provides a guy with an extra living room, a spotless living room unblessed with wives and children. When the plumbing goes on the blink, there’s no question of the waitress telling you to get up and fix it. She would never yank you out of your Nero Wolfe adventure with requests for a new row of shelves for Junior’s room. Nor will she hotly invite you to let your chess game fix your dinner.

It provides women with a place to sit in peace, and if some guy tries to hit on her, a slight smile and a nod toward the waiter is all it takes to cool him off. She can sit and read or talk with friends. There’s something about the atmosphere that puts people on their good behavior, the classy decor and muted conversations discourages the crude and rude.

That’s for the classic coffeehouse. There are dozens of other types, separated by class and occupation. The workers had theirs, where they would trudge in, very early in the morning, for the toilers’ breakfast of sausage and wine. Students had their favorites. Even pimps and hookers had theirs. I lived in an ill-heated flat in the Second District, a traditionally rough part of town, and the desire to write in a truly warm room took me to neighborhood cafes almost every night. One of them was unofficially reserved for hookers and tricks and pimps, and I wasn’t really welcome. But for some reason, it didn’t have canned music in the background, so I really wanted to stay there. Most of the hookers were pleasant enough, but not every single one of them.

Gertrude: “You making notes? What are you, asshole, a police informer?

Me: “No, not at all. I’m a –“

Gertrude: (Hearing my accent) “You’re a verdammt auslander. (Goddam foreigner.) What are you, English?”

Me: “American. And I’m simply—“

Gertrude: “Go back to your own pig-dog country. You’re writing shit. You’re writing shit about us. And then you think you can go back to your own shitty country and laugh about us.”

Me: “Oh yeah? What’s funny about you? What’s funny about anything? What is the purpose of existence, anyway?” Sometimes you can send a hostile conversation in a completely harmless direction by confusing your opponent.

Gertrude: “Hah?”

Me: “I mean, why do we live? What is the meaning of..”

Gertrude: “Go lick yourself, shit-hound. When Klaus gets back, he’s gonna shove your balls down your goddamed throat.”

And then sometimes you can’t.

I was interested in the Vienna style of life, and had been for years, but I actually went there mostly because Frank French, my old friend and bandmate from San Francisco, was there. He was gigging and working as a piano tuner, at which he excelled. I always considered myself lucky to be on the same stage, or even in the same room with him. All totaled up, we gigged together for about eight years.

We didn’t get that much work, however, and I ended up paying a few years’ worth of dues. We weren’t covering big hits, which people in all countries, all cultures, and all occupations except musicians prefer. So I had a rough couple of years there. Drum gigs were especially tough, as the little old ladies were really quick to call the cops every time they heard a drum anywhere. And the cops, working with a crime rate that compares favorably with villages in Switzerland, had nothing better to do than—er–investigate.

We did have some bright moments. We got booked to play a summer in Bodrum, Turkey. We played ragtime, actually, mostly Frank, who can outshine any musician that comes around. I just played with brushes and kept the beat. The Istanbul Charleston Society came to town—I am not kidding—and danced with us all night long. How many times does that happen to somebody?

Ahmet Ertegun’s summer home was next door to the bar. He and his brother Neshui came to hear us fairly often, and, considering who they were–founders of Atlantic Records–that was pretty bracing. These were the sons of the Turkish ambassador to the United States in the 1930s. They had come to America and been electrified by the MOBO in this country—not an unusual reaction, either. In the tradition of Chess and Blue Note Records, these young immigrants started a recording company to capture this stuff. This gave—well, sold—us the music of Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Bobby Darin and even, eventually, Led Zeppelin. Neshui was the only person who ever noticed that Frank was playing a correct but seldom-played chord in one of the Jelly Roll Morton tunes.

We were playing in Bodrum just after the Erteguns had signed the Rolling Stones, and the backpackers had discovered the fact that Mick Jagger had stayed at Ahmet’s house. Those that happened to be in Turkey would make a special trip to the town, find his house, stand on each others’ shoulders to peek over the wall into the garden that Mick had perhaps strolled through or had a smoke in.

Fame. I mean, really. Norman Lear, who used to write skits for Martin & Lewis, wrote about one groupie outside Jerry Lewis’ dressing room in the 1950s. He told her that Jerry was tired and couldn’t receive visitors. The young lady said something like, “In that case, I won’t disturb him. I’ll just pop in, blow him and leave.”

Back at the Turkish bar, I was happy enough to be playing for the Charleston dancers.

Back in Vienna, I was still paying my dues. Things got so tight I played on the street for about a year, which included winter. I played on the fussgangerzone, the pedestrian street. In Vienna it starts at the State Opera on the Kartnerstrasse, going past Stephansdom and continuing almost to the Danube Canal. It’s incredibly clean and prosperous, with tourists from every spot on Earth, horse-drawn cabs (fiacres), chestnut vendors, trendy shops from every spot on Earth. Entire tour buses would empty their charges out onto the street.

I joined the ranks of street musicians, one on every half block. They were a curious mix of classical virtuosity and scruffy wanderin’ folk singer types. Drums and amplification were prohibited, so I played a quiet percussion instrument that I, along with a friend/multi-instrumentalist named Charles Moselle, had sort of invented in San Francisco. It was a short box with copper tubes, tuned to a G minor and D minor scale. I played it with marimba mallets. It sounded not unlike the Balinese gamelan, and it was structured like an African balafon, so we named it Balibaliphone. (It can be heard on The Mirror of Simple Souls, under the Music link.)

I hit my stride in Vienna from about 1983 onwards. I started leading my own bands and playing piano gigs. I found a place that functioned as a bit of a paying clubhouse, a Vienna bar called the Roter Engel. (Red Angel)

The place was amazing. They had two different bands playing every night of the week, from 9:00 pm to 3:00 am. it was located in an all-night section of Vienna’s historic district called Der Bermuda Dreieck , or Bermuda Triangle, because it was possible for people to enter the place, hitting bar after bar, and not emerge for weeks.

I developed several bands on that stage. Wolfgang Beneder and Michael Satke, manager and owner, were good enough to let me just come to them with an idea, and they would give me some dates. It was actually some of the most creative fun I’ve ever had in the world of music. I played in the first Westbloc performance of Sergei Dreznin’s opera Ophelia, on that stage, and helped start the singing career of Kim Cooper, who went on to win a Eurovision song award. I think she has a PhD in African dance, something like that. I helped her put it to good use, giving her the role of lead singer The Darktown Whiteboys. I played drums with the incredibly gifted American singer/pianist Hannibal Means for about three years. He’s an easy and highly entertaining Google, and I recommend it.

I had, among many other time slots, the 1 am to 3 am solo piano Tuesday morning shift. Who’s out on the street, thirsty, looking to hear a band, at this hour? This is the sort of time we usually associate with coal miners waking up. But, by God, there were always people coming in. And they were usually, by then, so anesthesized with alcohol that I could play The Third Man theme for two hours straight and they wouldn’t notice anything wrong.

The Roter Engel is still there, but under new management, and they don’t have live music anymore. It went from being one of the coolest bars in Europe to just another unexciting watering hole with the stroke of a pen. But I got an e-mail from Wolfgang, in the summer of 2017, telling me that he and Michael were undertaking a book about the place, and would I contribute? Of course, I replied. I suppose that this is the start of that.

And it was. They sent me a finished copy, with a full page of my ranting and raving about their place…

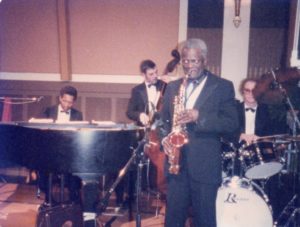

Four Americans, playing at a Viennese ball; Johnny Manhattan Taylor, p, Robert Goodenough, b, Leo Wright, sax, Me, drums

John Morrow. Irish Interlude.

I didn’t only vacation in North Africa. At one point I decided to visit Ireland, and I took the train. I found Dublin kind of despondent; there was a general air of failure about the place. The papers were full of accounts of street crime, and women would automatically clutch their handbags tighter as you approached. This happened, in fact, every single time I asked for street directions, and after a day or two of it, I just stopped asking. I mean, I already knew where the Guinness Brewery was, right next to the train station. I didn’t feel as though I needed much else.

I did manage to get to Parson’s Bookshop, but I can’t remember too much about it. The slightly famous co-proprieter, Mary King, wasn’t there, but I later read about her stories about Brendan Behan and Myles na Gopeleen.

Myles na Gopaleen was the pen name for the Irish writer Flann O’Brien (1911-1966), which was also a pen name. As an author, he is best known for The Third Policeman and At Swim Two Birds. Although they were praised by writers as accomplished as Graham Greene and Jorge Luis Borges, I didn’t really get a feel for those novels, and didn’t finish either of them. But I came across The Best of Myles, which was a compilation of the columns he wrote for the Irish Times. He wrote mostly about Dublin, starting in 1940, when Ireland was a neutral party in WWII. From the third page I could see that I was dealing with a literary genius, telling me more about Irish life in a paragraph than others had in full chapters. His humor is pained and twisted, full of tribal self-exasperation, as Irish humor so often is. His short essays about the eternal Irish everyman Paddy, who is merely stumbling along, battered and sent into every direction by the incomprehensible forces of the real world, seemed to catch the Gaelic condition better than anything.

Myles also traveled on the continent a bit, and in the 1930s, found himself in a train overlooking the Donau (Danube) River, sitting next to a pedantic, professorial German. Anxious to try out his own, schoolboy German, he asked the professor, “Das ist der Donau?” he asked. “Nein,” the professor snapped. “Das ist die Donau.”

I had heard that Mary had actually known him. She described him, in an interview, as “quite an insignificant looking character; it’s funny, you didn’t get the spark, it all went into his writing.” Brendan Behan once nodded. “There you have him!”

Swim Two Birds, in this century, is the name of a cutting-edge music studio in D.C.

I’d made a couple of pub pals, and I told them that my next stop was Belfast, Northern Ireland. This was during a particularly vicious iteration of “The Troubles,” where the Taigs and the Prods were at it again. My friends in Dublin said, very solemnly, “Well, good-bye, then.”

Not, “see ya later,” or “until next time.”

BELFAST, however, was cheerful and popping. And of course exploding. The city was a battlefield, according to press reports. If that was the case, the residents had happily adopted the “eat drink and be merry” mindset, figuring that if a bomb is going to go off during dessert, one might as well have a good time with the entrée.

There were street musicians, street corner poets, a couple of pedestrian streets, and full-to-bursting pubs. I saw more smiles in an hour than in Dublin in a week.

A friend and colleague in Vienna, an Irishman named Denn Warrick, had grown up in Belfast. He had been, in fact, Van Morrison’s chaperone, as the barely teenaged Van was starting up, singing and strumming his way through the music pubs. He—Denn–became a well-known Irish tenor in London, and always seemed to be participating in historical musical moments well ahead of the rest of the world. He saw the Beatles, live, in a high school gymnasium in Liverpool, for instance.

He was also a good friend of John Morrow, the Northern Irish black humorist, and he gave me a copy of The Confessions of Pronsious O’Toole for background. I loved it; it was skillfully crafted, with a mordant eye for the human greed of the British and the IRA, puncturing the pomposity and rhetoric of revolutionaries. No matter what sort of utopian society people are fighting for, they never forget that they’re also pursuing a path to money and power. And that generally overtakes everything else.

Anthony Thwaite—I say, there’s a Brit—wrote that John sounded “like a Belfast Tom Sharpe.” Christopher Wordsworth—and there’s another—writing in The Guardian, said that Morrow “gouges a great deal of fun from the troubles of his native land…”

Well, I gave him a call. I was finishing up the Leo Wright book at the time so I figured I had a bit of literary cred. I needn’t have bothered bringing any of that up; his oldest son is a drummer.

We met at the Crown Bar, in the center of town. It was one of the very last gaslit pubs in Europe. We had a good chat, and he gave me a copy of Sects and Other Stories, a collection of short stories that I still have and will always recommend.

John left school at 14 and started his working life working as a navvy—day laborer–in the Belfast shipyards. Pushed along by the sort of brilliance that goes through obstacles of class and circumstance, he started submitting comic pieces to local journals. He eventually got a wonderful day job on the Belfast Arts Council as Director of Combined Arts, with responsibility for literature and community arts. And he brought out book after book, all of them well worth it.

John died in 2014, at 84. Damian Smyth, who became the Arts Council’s head of literature & drama, said,

“This is a sad morning for the arts in Northern Ireland.”

John Morrow, Belfast, ca. 1985

Sure an they do party in the pubs every night. Belfast, late 1980s…

Not More Hookers?

I think I have one more whorehouse anecdote. This time I wasn’t a customer, but a drummer on the job. Something about male behavior toward hookers lends itself to the anecdotal life. I wrote this piece with an eye toward SCREW, but I never sent it in, and I can’t remember why. Anyway:

La Paloma

Among the sadly vanishing professions, like bookbinder and bootmaker, is the honorable trade of whorehouse musician. Brothels, hounded by cops and puritans in the United States and taxmen in Europe, aren’t offering the same old courtly hospitality. Like bars, nightclubs and even airports, they have replaced pianos with machinery. I guess we can say that the planet has replaced elegance with things activated by plastic buttons, and it’s another shame in a century already bursting with them.

A lot of master musicians learned their trade in cathouses. Jelly Roll Morton and Buddy Bolden and in fact Louis Armstrong come to mind, but Johannes Brahms did as well. Think about that. Johannes Brahms, one of the most conservative composers that ever lived, a square even by the standards of his old-fashioned world, spent his early teens in whore-bashing taverns in Hamburg, grinding out pop tunes for drunken sailors. I have read that he found the routine so boring that he read a book while he was playing.

This had been a very welcome piece of news to me. Every time I run across an instance of some respectable pillar of society doing something twisted and human, I don’t feel like such a pervert. And if the composer of Darthula’s Grabengesang could play sailor chanties at Madame Heidi’s, so could I. And worse.

One of the steadier gigs I had was playing congas with a Dominican named Alfredo Ventilla. He played guitar, sang, and moved his hips in a manner that excited the pale blonde ladies that came around. Between sets he would troll the audience, recruiting them. He would go to the girl closest to the stage, look into her eyes, tell her that he had sung that song, “Yust for you, presciosa,” and invite her backstage for a quick one. If she didn’t care to he would simply go to the next table, locate someone female, look into her eyes, and tell her, without the slightest hint of irony, that he had sung that song yust for her. Presciosa. And so on and so on. It may seem a laborious, gold-panning process, as random as the odds of a single sperm cell, but nature’s like that. It worked well enough for him. Once he kept us waiting almost an hour in an ill-heated dressing room while he screwed a fraulein in a god-damned closet.

The Dominican Republic, by the way, is the home of Porfirio Rubirosa, who by all accounts was the most capable playah that ever scorched a sheet. A child of the Dominican oligarchy, his father was the island’s ambassador to France in the 1920s, exposing young Porfirio to a churning sea of jazz-age nightclubs and bordellos, the absolute perfect kind of backdrop for his particular talents.

The times make the man. It was true with the American founding fathers. There were probably millions of guys just as clever and heroic, but had they lived in 12th century Umbria, they would have gone from cradle to grave working in the mines. With our guys, Jefferson, Franklin, the world that bred them and the chance to graft a new society onto it was what activated them. How many potential Porfirios languished cutting sugar cane for European planters is something we’ll never know. But Porfirio was the lucky one, of all those sperm cells. He would go on to marry some of the richest women in the world and have affairs with most of the others. Indeed, by a judicious poking of one of Trujillo’s daughters, he was appointed ambassador to Cuba in the 1950s. There, legend has it, while his hotel was attacked and bombed by Castro’s rebels, he continued servicing one of the maids.

So, I mean, Alfredo was a good guy and a good musician, but he was hostage to his heritage, and he chased girls with the same unthinking resolve as a shark gobbling mackerels. I ultimately played with three different Dominican bandleaders while I was in Europe, and it was pretty much the same thing.

We were on tour in Bavaria, and we reached a town I will call Donglsdorf. It was a remarkably ugly place. It was a factory town, holding quite a few foreign workers, who sent money back to their families in Yugoslavia or Turkey or even Senegal. And when these guys, alone, living in bunk beds in what were almost barracks, came off of their shifts, they were not going to spend any money on the films of Werner Herzog. This created a void that bordello keepers could smell through the factory smoke.

A Serbian Gypsy, Darko by name, had tossed a bootie bar up across from the factory gates. After every shift, a good-sized group of workers would tramp in, grunting, select a girl, and swap a bottle of overpriced “champagne” for a hand job under the table.

“Very clean place,” remarked Gerhard, who played bongos. “No stains.”

Darko, who ran the place, was an excellent guy, by every standard except possibly legal ones. And compared to others who run nightclubs he was Mother Teresa. The minute we arrived he took us to a Gaasthaus and blew us to the biggest meal we’d seen since our first communions. This included personal bottles of schnaaps and some big cigars. He was the kind of hearty, burly, mustached type who slaps you on the back and laughs a lot; every inch the jolly godfather of the worker’s sector. We were all hung over, dismal and road weary, but even through our touring fog we caught a glimmer of a man that was going to enjoy his stay on the planet. And we, for our brief time in his radius, were invited to join up.

I hadn’t come alone. During an earlier tour Gerhard and I had made the acquaintance of a pair of sisters who lived in Munich, and under the principle of A Girl In Every Port we had made ourselves welcome, nonpaying guests whenever we came to town. Musicians treasure these liaisons. It’s good for the ego, which can take a bruising on the road, to have friends to go to. My particular friend, Andrea, was a bright, agreeable woman in her late 20s, and her house was home to more musical instruments than mine. But it was understood that during those seven or 10 days a year when I stayed under her roof, we were a couple. This was to have some unusual consequences in the hours ahead.

Darko made an announcement. All of his bar girls possessed an undiscovered theatrical genius. He wanted the drummers to lay out a duet while the ladies performed “A piece theatre they create by self!” Gerhard and I took a drum spot and one of the ladies, emoting powerfully, shoved a bottle of tequila up between her legs.

Wow, said I. The kind of artistic challenge you don’t get every day.

The next girl came on. She was French and her name was Marie, and she was wearing one of those maid’s uniforms from MGM movies. She, too, had an undiscovered theatrical talent. She could pick up a 50-mark note—nothing smaller—from the stage with her pussy. A guy came up, and with an alcoholic flourish, tossed a 50 on the stage. She writhed and squirmed and failed totally, cursing. Then she snatched it up with her hand and stuck it in, took a bow, and scooted off. The poor guy just stood there, looking bewildered, yet another example of exploitation of the workers.

I’ve mentioned that our two friends had been putting us up for the week, and in this case they had also accompanied us to the gig. They were nice, respectable German liberals and their only contact with hookers had been through sociology courses and feminist group discussions. Now they were testing their theories against reality, and they didn’t look too happy. They were sitting around, nursing cokes, wearing glasses, taking notes, about as likely to join in the general deviltry as John Knox.

Alfredo came over. He wanted to pull a trick that he knew from Spain, and the rest of us should just relax. Knowing Alfredo, I found this far from relaxing. He was probably going to grab a half dozen bar girls, start some kind of territorial brawl that I would have fight while he slipped over to the restaurant across the street and diddled the waitress. But I was wrong. It was worse. He wanted to take his guitar over to Darko’s table and sing La Paloma.

I don’t know if you’re aware of this song, but it’s one of the corniest songs in a mileau—sentimental pop—that already has enough corn to feed all of East Africa. The title means “The Pigeon,” and there’s a little bird call tossed in at the chorus. One should “Coo” it. One sings, “Koo Koo Roo Koo Koo, Paloma,” with great passion. I’d only heard it once before, when it was being parodied by Carla Bley. And I didn’t even like it then.

And, as far as that goes, I don’t care that much for pigeons in the first place. They seem to be the least enjoyable members of the aviary; the catfish of our public parks, the garbage scows of the bird world. They fly around like a plague of bats and they bestow turds upon your collar. Any time you try to feed a real bird the god-damned pigeons are jumping the queue, opening their beaks like Third World politicians. And here goes Alfredo, going out of his way to imitate them.

He went over to Darko’s table and started crooning. He pulled out all the stops. Every time he got to the Koo Koo Roo Koo Koo he made it sound like a lament to his dying mother. And they loved it. Soon the whole table was in tears. And the table was not holding sentimental sissies. That town held a lot of hard-ass Gypsies and aggressive German entrepreneurial types who would have loved to move in on Darko’s action; a perceived weakling would have been chased out of town years before. Darko, like my brilliant capitalist uncle in Detroit, was still standing.

His tablemates were evil-looking Gypsies or thick-necked, scarfaced Germans with shaven skulls. Within five minutes Alfredo had them crying like contestants on Queen for a Day. I groaned. Shamelessness seems to be as effective in music as it is in politics. And soon, every time he Koo Koo Roo Koo Kooed Darko would whip out a hundred marks and tearfully shove it into Alfredo’s pocket.

Even Andrea and her sister enjoyed it. They were entertained more by the sight of grown men weeping and tossing money at bird calls, but whatever makes you happy makes you happy. I however, couldn’t stand it. I couldn’t stand the dumb-ass song and I couldn’t stand the spectacle of our bandleader making a commercial success out of himself and I especially couldn’t stand the thought of him getting all those 100 mark notes that he wouldn’t have to split with the rhythm section. I headed out of earshot.

On my way, though, I saw Marie, who was having a quiet smoke. I joined her, smiling ironically, the Kookoorookookoos wafting around like farts in a tunnel. She smiled ironically back.

“Votre femme ecoute le sauvage,” she told me. My French, by the way, is even worse than my German.

“Le Sauvage? Vous mean Alfredo?”

“Non. Darko, le Gitane. Votre femme et un tout a fait boche.” This meant, “Your woman is a typical kraut,” although I didn’t know it at the time. I replied using the same method I use with every foreign language, by guessing.

“Jealous? Elle? Don’t be silly. N’est pas la comique. She n’est pas la knife. Non sweat. Don’t n’est pas get la bug up votre derriere. Nous be safe as lait.”

“Kookoorookookoo, Pa-LO-ma…” came rolling out of the bar. I heard a howl of schadenfreude and the smack of another banknote on the table. Two weeks before I had taken a piano spot and played a Sidney Bechet tune that I’d practiced for a full week and I hadn’t made a single mistake. Nobody clapped. Most of them hadn’t even known that someone was playing anything. One of the few who did howled out for “Strangers in the Night.”

“Kookoorookookoo, Pa-LO-ma…” Alfredo was making it sound uglier than whoever wrote it. He put a hitch in his voice that sounded like a grease rack going up. It reeked of a greasy pimp in a Mexican roadhouse, with cheap perfume and slicked-down hair and painted fingernails, twirling his mustache and threatening his newest 12-year old. Of brassy whores, knifing each other for the chance to go through your pockets. Of fat, sweaty, drunken federales, stumbling in for their nightly payoffs…

“Nous et okay, Marie. Ma femme she ecoute la chanson de pigeon.”

“Hooray,” she mumbled. It was hard to tell how she meant that.

“Kookoorookookoo, koKOO!!!!” A huge burst of sobs, laughs, moans and applause roared in, and it sounded ominously like the finale. Darko, through his tears, bellowed for his girls, like Old King Cole demanding his fiddlers. Marie bolted for his table at the speed of a cartoon rabbit.

I went over and joined the pigeon fanciers. Andrea, having had a good laugh at the expense of the male species, was in a far better mood. Alfredo, of course, was smug, insufferable, and made a point of letting me know that this sort of shameless tripe was where the band’s repertoire should go.

EPILOGUE

Alfredo, taking Darko up on his offer, went off with two of the bar girls and disappeared until 73 minutes before the next night’s gig. As soon as he had reached their flat, he went into the bathroom to “perfume myself,” and fell asleep in the bathtub. The bar girls, suddenly off duty, made no attempt to rouse him and went to bed in each other’s arms, enjoying a hearty laugh at the expense of the male species. And Alfredo’s tips, something close to 1,000 marks dangling out of his pants pocket, were still there when he woke up.

“Darko’s girls,” our patron had told us, “is good girls.” And so they were.

Salzburg, 2000. This traditional Austrian oom-pah band is performing the Woodchopper’s Dance for tourists from all over the world. This band had been playing there, seven nights a week, since…1964! The leader’s sons and grandsons had gone into the family “business…”

“Why can’t we all get along?” answered. Vienna, Mariahilferstrasse. Bondage shop doing its business peaceably next to a children’s clothing shop…

TO BE CONTINUED, IN VIENNA 2

Comments

Leave a Reply

*

Be the first to comment.