HAVE DRUM, WILL TRAVEL

Chapter One

The Hounds of Fate

or

How J.B. Priestly Primed me for North Africa

Vienna, winter 1986. I’m standing on Naglergasse

In the 1980s, I was an ex-pat in Vienna, making an anxious living as a free-lance musician. I lived in the Leopoldstadt, the Second District, a close-in area that was, until Hitler, the city’s Jewish quarter. A few Jews had returned after the war, but the defeated, shell-shocked remnants of the master race weren’t all that welcoming, and it wasn’t a very popular destination. Instead, it filled up with working-class emigrants from Eastern Europe and the Austrian countryside. By the time I got there its character was about as Jewish as Ovaltine.

It was the safest inner city I had ever seen. The apartment buildings and retail shops were almost fully occupied and prospering, and women could walk alone, tipsy and unmolested, any hour of the night. Little old ladies would scold teenagers, right on the street, for sloppy attire. And the kids would apologize.

By the conservative, obedient standards of Central Europe, however, the Second District was the wrong side of the tracks. Drunks would stumble along the Praterstern, cursing something or other, and this might lead to a fistfight with some other drunk who was cursing something else. A few of the cheaper hotels functioned as brothels. And that was about it. But to the proper Viennese burghers, who had never experienced muggers and street crime, it might as well have been the South Bronx.

Brahms had lived on my street, a century earlier. I understand that he had been kicked out of place after place for making too much noise. The Germanic fetish for ruhe—a mixture of peace, quiet and utter submission to the notions of the little old lady upstairs–had tyrannized even this most conservative of classical composers. And I could believe it. A young woman I know was evicted for running her tapwater after 9:00 pm. So I spent a lot of time reading, being careful not to make too much noise turning the pages.

English language books were expensive and not easily found, so I spent hours borrowing from the library of the British Council, exploring the almost endless bounty of English letters. Besides heavy hitters like Dickens and Maugham, I got to know writers I had never heard about in America, people like Anthony Trollope, Gwyn Griffin, and Samuel Butler. Then there was H.H. Munro, a.k.a. Saki, the absolute master of the short story, who, before he was killed by a German sniper in 1916, gave me the title of this piece.

I discovered novelists from the Golden Age of British mystery—mostly the 1920s through the ’40s– writers like Michael Innes and Edmund Crispin (aka J.L.M. Stewart and Bruce Montgomery), and I admit to reading titles like Crime Wave at Little Cornford and Fear Comes to Chalfont. One Leo Bruce—aka Rupert Croft-Cooke–created Sgt. Beef, star of Case Without a Corpse.

But it was with J.B. Priestly (1894-1984), who didn’t write mysteries, that I found my level. His thoughtful essays, picaresque novels, insightful non-fiction and stunning metaphors seemed to settle in right along the thoughts that I was heading toward but hadn’t quite formed. I had given up driving during the Carter administration; he penned Carless at Last in 1928, writing about “sneering and shrugging attendants in overalls…and bills for repairs that are as crazy and vindictive as the proclamations of Oriental tyrants.” I stopped listening to recorded music in 1983, he had articulated my reasoning in 1949; “Every time a violin is taken up to the lumber room, a piano is carted away, and in their place is a gadget that turns music on and off like tap water, we move another step away from sanity and take to snarling harder than ever.” Literary history has classified him as a middlebrow, and when I read that I learned where my particular brow was positioned.

In the 1920s he wrote an essay about a miserable, soggy trip through Wales. It went from a dangerous, rain-soaked horror to a fire-lit haven, thanks to his arrival at a lakeside fisherman’s inn. It was the type of idyllic, wood and brass alehouse we would read about in Henry Fielding and was becoming a bulldozer’s soft target even then. It was so redolent of the 19th century that he called it “a combination of The Pickwick Papers and The Compleat Angler.” It must have looked like a mirage upon approach, with golden lights twinkling through the storm, like the cabin of a ship at sea. “There never was a better journey’s end,” he wrote.

It reminded me of a journey’s end of my own.

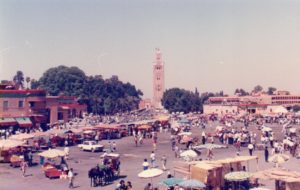

January was always a slow month for music in Vienna, and I’d made a habit of spending that month in North Africa. I’d take trains through Italy or France and, one way or another, end up in Morocco. I enjoyed Islamic countries, or at least in small doses. After playing for drunks and inviting random women backstage 11 months out of the year, I found a certain pleasant balance in societies where alcohol wasn’t the lubricant of choice and trying to pick up women would get you about as far as it would in 19th century Scotland. The “stage” was usually Jamal Neuf Square, the outdoor performance/flea market/Speaker’s Corner in Marrakech. There haven’t been many American drummers that have played with Moroccan snake charmers, but I’m one of them.

Marrakech, Jamal Neuf Square

Storyteller in the Square

I usually disembarked in Tunisia, a fine little place that always treated me well. So well, in fact, that I don’t have a single story about the place. I took a train to Algiers.

Algeria was fairly safe, back then. This was before the spectacular incompetence of its government helped produce the cutthroat Islamist insurgency it’s become known for. But I still managed to get mugged—badly– in Algiers, attacked by a female lunatic in Tclemsen, and find myself the unwitting source of a vicious police attack on a teenage girl who had asked me to help with her English.

Beyond that, it was boring. In fact, Algeria was the most boring country I had ever visited, a title it still holds. The FLN, (Fronte de Liberation Nationale) which still runs the country, is a nervous mixture of theocracy and socialism–with all of the drawbacks of both—and almost everything was either Haraam or Contrary to the Revolutionary Will of the People.

Morocco, on the other hand, despite all the—quite true—horror stories about backpackers getting robbed or swindled or panhandled half to death, was and is a wonderful place, and I spent five consecutive Januaries there, always sorry to leave.

In a fine little town called Oujda, I boarded a bus to Fez. After we got underway, with the usual happy bustle that comes with loading pallets of sugar onto the roof and escorting goats into the seating area, it started to snow. Nobody could believe it, in fact most Moroccans had never even seen snow. The bus itself was about as ready for cold weather as a canoe full of Tahitians.

This bus was a great argument for train travel, or even skateboarding. The heater didn’t work, if indeed there was one at all. The cold was creeping in from the rattling floorboards and cracked windows, and soon it was the defining aspect of the bus.

So went 10 lurching, miserable hours. I had smoked all of my kif, which, anyway, provides no warmth, and smashed my frozen feet against the crumbling floorboards long enough to start a new dance craze, and still the god-damned bus lurched on, stopping here and there for gas and repairs (although not to the heating system). And my seat partner kept bashing his goat over the head.

Years later, in Washington, D.C., I heard Paul Theroux give a talk at the National Press Club. He said that journeys, real traveling, should not be easy. I agree, it can’t be. You’re pushing your way into a foreign space, one that wasn’t particularly designed for you, and a series of bumps and whacks is pretty much inevitable. He mentioned Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s The Worst Journey in the World, a well-named tale of a frozen side journey during Robert Falcon Scott’s fatal Antarctic Expedition in 1910. I immediately thought about that bus ride. That chilly memory jumped right to the head of the queue, beating out:

–Nine hours in an African bush taxi, through a whole lot of the Malian desert, stuffed, with eight other people, into a compact Puegeot,

–A bus ride that skirted the edges of Himalayan roads just a bit wider than a rattlesnake,

–Hiding on the floor of a Nigerian taxi during anti-foreigner riots,

–A half-day stuck in a Sri Lankan rush hour, and

–23 hours on a milk train from Pakistan to India, with a head full of opium, where beggars, generally deformed with elephantiasis, boarded at every stop, pleading for coins.

Mr. Theroux has certainly had more adventures and traveler’s misery than I have, but his talk gave me some perspective. I only wish I had heard it before I got on that bus.

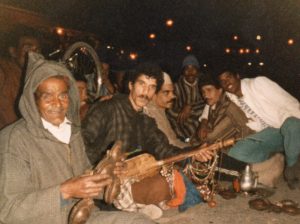

Playing with Moroccan Drummers,Winter, 1983

Harbor, Essouria, 1989.

Good friends, Moroccan Gnoua players. They played all day, into the evening, seven days a week. It put them into a smiling mood…

The end of this journey was heralded by a glimpse of the lights of Fez, and it was a sight worth a lot of suffering. For Fez rests on a hill and the lights are yellow-gold, illuminating the ancient walls and glowing golden against the night. We were filled with awe and relief, and the knowledge that we were entering the reward phase of the trip.

And so it was. The bus stopped at a beautiful, warm, nicely-lit cafe, bustling with smiling people and steaming with tea and coffee. It had huge glass windows, soft golden lights and wooden tables, and was packed with satisfied-looking customers. The teapots and samovars were either highly polished brass or something that looked like pewter. The water was on a slow boil over an open fire, which heated the whole room. It featured a level of technical development–burning coals, radios playing live, local music—which was not unlike what my idea of what the past was like. Wales, in the 1920’s, for instance.

I decided to live there.

In one of his short stories, Somerset Maugham wrote about destiny and fate pulling one toward unexpected spots, quite independent of the thinking process. A gentleman from the London Stock Exchange is traveling around on a 14-day Cook’s Tour of Istanbul and something hits him; some sort of race memory kicks in and he suddenly sees Istanbul not as a tourist spot but as a familiar place, one where part of him has always lived. It was, in fact, his true home. His entire life and previous training had been an unwitting exile, and his true destiny was the life of a fruit peddler in Uskudar.

He can live here, he thinks. He has a mercantile mind, he can live by trade just like these folks do. He deserts his tour bus, buys a crate full of peaches and gets to work. He becomes a fulfilled man. He is in his assigned place.

A few years later, some colleagues from his old days at the stock exchange are passing through and notice something familiar in that ragged vendor in the last stall. They mutter, “I’m dashed if that fruit vendor doesn’t remind one of old Bill Tweep.”

They question him. Ah yes, effendi, he replies, he was once Bill Tweep. But now his name is Ali Guzel. He explains that he was directed to this spot and this life by forces he has never understood, and has never begun to comprehend. But it is his place. All he could do was bow to its superior wisdom and follow.

Then he says goodbye, overcharges them for a peach, and sits back and chuckles about it. Finally, he cackles, I got the better of those two bastards in a business deal. And the hounds of fate are, for once, content.

So I felt it to be with myself. Nothing could drive me from that cafe. I would live upstairs and wait on tables and organize late night drum sessions. I had it all worked out before my first refill. And then another hound of fate sat down next to me.

“You will show me ze passez-port!” he commanded. Fate’s hound was big, oily, generously mustached, with angry cop’s eyes. “I am wiz ze gendarmarie. Les especial poh-leez!”

I sighed—at my low-rent level of international travel the annoying characters flock after you like buzzards–and asked him if I could see his police identification. I do this a lot. It’s a fair bet that about half of the Developing World “policemen” that hit on you are hustlers, and by this time I was giving them as much credibility as Elvis impersonators.

“I am wiz ze especial poh-leez,” he snapped. “I no need les identifications!” (I doan need no stinkin’ badges!)

“Yes, sir,” I said, quite relieved, pegging him as one of the Hound Dog tribe. I didn’t dig my passport out, but I put a helpful, cooperative look on my face. I do this a lot, too. It was apparently enough.

“Tres bien,” he replied, quite amiably. “So, now you buy me tea, and I will in-terr-o-gatez vous.”

“Of course,” I said. I figured that a phony Moroccan third degree might be worth a free drink. So I ordered another. I started thinking, for whatever reason, how I would handle an interrogation from Sgt. Beef.

The policeman smiled. He leaned closer, and I noticed that his oiliness seemed to come from some sort of lotion that he had smeared himself with. He was also heavily perfumed. I was starting to enjoy this. It was becoming silly, and if people are silly I can overlook a lot of other character flaws.

“Question ze first,” he said. “Question ze first is….did you see yesterday ze football match?”

Now, that seemed an unlikely place to start an interrogation. Normally, North African policemen start off with a passing remark about the Islamic penalties for hashish smuggling. Hand chopping is also mentioned. Public flogging is lovingly described. But then I thought that maybe he was actually one of those clever, devious inquisitors. The type that gets you into a relaxed frame of mind, and just as you’re gaily chattering on about the home team they’ll cut in with, “But wheredja stash the corpse, Lefty??” So I buttoned my lip.

“Ze football game! Ze soccer match!!” he shouted, impatiently. “Ze bloody big football game between wonderful heavenly Morocco and pestilence-ridden camel dung Algeria!!”

Actually I had seen that. In the two countries only the dead hadn’t, and everybody was talking about it. I had witnessed it in a one-room cafe in Oujda, along with what seemed like four thousand others. At that time, Algeria and Morocco were fighting a desultory little border war over certain key sand piles in the Spanish Sahara. The reasons for the war have always escaped me—I think it had something to do with phosphate–but it did give a real tang of blood to the sporting events. The agonized screams and hair-rending at every Algerian goal were the kind you’d associate with unsuccessful plastic surgery. So, okay, I had seen the game and Morocco had lost. And by that time the guys in the cafe had worked themselves up into such a howling pitch of xenophobia that I ran out the back door and got on the first bus I could find. I explained this to the especial policeman and added that I felt rotten about it. Damn sad, that’s how you could have described me.

He was, too. His eyes were moist with pity. He was heartbroken. Then, to show me that we were brothers in this terrible calamity, he put his hand on my knee.

“Let us go to Turkish bath,” he said, softly. “There, I will further in-terror-gatez vous.”

Ah, well. I had seen it coming, kinda. It’s a flat hustle that was probably ancient in the time of Leonardo da Vinci. I wasn’t surprised, but I was disappointed. I wanted this encounter to stay on the silly side.

At that point one of the waiters brought the policeman’s tea. Speaking respectfully, and phrasing it differently, he explained that this man was the neighborhood loony. He had been in an automobile accident and lost several of his marbles. It made him feel good to impersonate a policeman and use that to bum drinks and maybe take a traveler into the Turkish bath now and then. The other patrons tolerated him, finding him slightly amusing. But please, the waiter said, do not judge my country by this man’s behavior.

I nodded, but I actually did judge his country by this man’s behavior. And it came out way on top. He and his fellows were exhibiting a level of kindness and tolerance that a lot of other cultures hadn’t tumbled to just then. The especial policeman, perhaps gay and definitely crazed, hadn’t been attacked by gangs of skinheads. He still had all his teeth. The government hadn’t publicly executed him for abominations. Televangelists weren’t publicly shaming him.

I turned to the especial policeman. I figured that it was best to take this man on his terms. He was a part of the cafe and I wanted to be a part of the place as well.

“I confess,” I said. “You got me dead to rights, guv,” I almost added. I would have if I’d thought that he was a fan of Sgt. Beef.

I took out some money and handed it to him. “I know what this is about, officer. You want a bribe to make the charges go away.”

I’m not sure he understood that, but he accepted the money readily enough, smiled, picked up his tea and moved to another table. I was left in peace.

Could this have happened to Priestley’s anglers? Could the village idiot have also hung out at their mystical Inn? There probably wasn’t a Turkish bath next door, but, you know…

Priestly ended his essay with the thought that his experience at the inn was more like a “leisurely old-fashioned tale than a piece of reality…that showed me, in the jazz pattern of our years, this silver thread of peaceful and quiet days that old Isaak Walton knew so long ago.” He doubted that he could ever find the place again, and was sure that it would vanish forever.

I didn’t move in upstairs, of course. I couldn’t see myself taking any kind of job away from Morocco’s endless line of young, unemployed men, even if I could. I went back to Europe and resumed my personal folly.

I returned to Fez about 10 years later. From 25 miles out, I started scanning the city for yellow-gold lights, the wooden cafe, the steaming samovars; as anxious as if I were reconnecting with a lost child.

I couldn’t find it either.

Some pix I just like, for no apparent reason. Marakkech

Nut vendor, Marrakech, Winter

Tangiers coast

Comments

Leave a Reply

*

Be the first to comment.