D.C. 1990 — PRESENT

With vocalist, educator and former Washington Redskin Dick Smith.

Playing timbales in Malcolm X Park

I selected Washington D.C. because my recently widowed mother had moved there, and I wanted to go through the motions of filial devotion. She ended up getting married again–this time to a trombonist from the same big band my father had played in. Wow, I thought. What is it about those Canadian brass players?

So, all this meant that I could move to any other place I felt like. But by then I was enjoying the city. I had been selling some free-lance pieces here and there, I was getting into the world of journalism, and I was really having fun listening to the politicians on Capitol Hill. Daniel Patrick Moynihan was always a treat, one of the coolest guys I have ever listened to. The congressional elections of 1994, of course, pretty much ruined the class and wit that had gone before it.

But not completely. I thought, for the longest time, that this batch of square-ass Republicans could never bring the dialogue up to the level of a Tip O’Neil, who once described Ronald Reagan’s Irish ancestral digs as “The valley of the small potatoes.”

I was wrong. During Bill Clinton’s presidency, some Republican wag said that the president was “doing the job of three men: Larry, Moe and Curly.”

Anyway, the city was prosperous and the denizens were accomplished, intelligent and one would think that they needed to hear some live music to unwind after a hard day of battling budget cutters. As one of the several self-designated “Chocolate Cities” in the country, there was certainly no danger of the city itself being too white. So I figured I could kind of day-job my way around town, and go off on trips in between them. And I could and I did.

The city, being over 50 percent African-American, wasn’t of course completely prosperous. The income disparity between black and white residents was and is the highest in the United States. The U.S. Census puts black median income at less than one-third of that of whites, or $37,891 to for white families, $127,369 for whites. This is not good for a society in the long-term, but for me it meant that there were at least affordable rooms available, if I didn’t mind living in the ghetto. I didn’t, of course, and I never have, so I took a furnished room on 11th Street Northwest, a walk of a mile or so to Adams-Morgan, one of D.C.’s nightlife neighborhoods. It was an okay neighborhood, but, like most ghettos, there weren’t too many shops or cafes or pretty much anything else. There was a once-thriving business district further up 11th, and I knew this because all of the first-floor real estate was a slew of boarded up shops. Dope dealers hung out here and there, winos passed out in what were once doorways and even the liquor stores seemed to be having a hard time of it. But my first morning there, I got treated to something anthropological.

Just outside my window, in an abandoned garage in the alley, some enterprising fellow had set up a still. Not the Appalachian kind; it was just a stash for a batch of liquor he sold before the liquor stores opened. His target demographic was the guys who couldn’t possibly wait until 9:00 am to start their day’s boozing, so it wasn’t a particularly refined crowd. Their speech was slurred, they were argumentative, and what ideas I could make out were pedestrian. But they all spoke at the same time, and it all seemed to be a variation on the word “motherfucker,” or “muvfuggah.” By the time it all wafted up to my window it sounded like a muvfuggah chorus in some opera. The Twilight of da Muvfuggahz, something like that. One of the other room renters apologized for the “sinful noise” every morning, but I told him that I truly enjoyed it, and if my window had opened out on the street I would wake up to the sound of trucks shifting into first gear.

I wasn’t sure what I could compare it to until I read Ralph Ellison’s Living with Music, a posthumous collection of his essays and music reviews. In it, he wrote about an alley behind his own cheap flat during the early 1920s in Oklahoma City:

“But the court behind the wall…was a forum for various singing and/or preaching drunks who wandered back from the corner bar…the preaching drunks took on any topic that came to mind: current events, the fate of the long-sunk Titanic, or the relative merits of the Giants and the Dodgers. Naturally there was great argument and occasional fighting–none of it fatal but all of it loud.

I shouldn’t complain, however, for these were rather entertaining drunks, who, like the birds, appeared in the spring and left with the first fall cold.”

As for me, it was the first and only time I ever found drunks to be in any way entertaining. And, as to the rest of the Ellison book, he compared Charlie Parker to Francois Villon, and stated that, in his day, in the South, a black man could be–and had been–lynched for painting his own house. I’ll keep that one handy for the next time some Repugnican starts talking about “A simpler, better time…”

MUSIC IN D.C. part one

Christopher Isherwood once said, in an interview, that he couldn’t go more than a few days without the company of other gay people. “It’s like oxygen,” he said. I feel the same way about the company of musicians. Musicians, especially jazz or worldbeat musicians, have, as Lenny Bruce said, an appreciation of the abstract and the absurd. This is one of the primal urges that makes Bohemia tick.

I also think white musicians become better when they are surrounded and influenced by African-American musicians. I would consider the latter to be the absolute gold standard of musical excellence, and I challenge anyone to come up with a better qualified group of people anywhere. That includes Africa. African-American musicians have what seems to be an extra 10 percent of ability, which strikes me as magic, really. Some cosmic gift, brought about by the same incomprehensible forces of nature and nurture have given us wisecracking Jews and silver-tongued Irish.

Ralph Berton, who wrote a wonderful bio of Bix Beiderbecke (“Remembering Bix” 1974) writing about the jazz age, said that there didn’t seem to be anything special about the black musicians he met, they came off just like anybody else. Playing music brilliantly was just something else they did, like stamp collecting. The white guys, however, apparently needed to have been infected with some sort of oddball gene; it was apparently the necessary boost that they needed to play in that league. Bix, of course, was the classic example. I suppose I might qualify myself, actually, at least with the oddball part.

When I was interviewing Leo Wright, I asked him why it was always the black musicians that were such musical innovators, taking sounds and grooves to uncharted places, and sticking with it. They would do this even when they saw that the public wasn’t ready for it, and there wasn’t any money to be had from it. “For black people,” he said “Bein’ poor ain’t nothin’ new. If the music’s worth it, we can take it.”

I started playing music in D.C. at street level. I discovered an African-American drum circle in one of the bigger city parks. It turned out to be a legendary spot, although I’d never heard of it, but one that I would adopt. It turned out that there has been a serious drum circle in this park since the 1960s. Up to and through the riots, every Sunday, the guys would show up, bringing drums, knowledge and brotherhood. All I had to do was integrate it.

Everyone was African-American, and I certainly got a lot of curious looks when I showed up. But that’s all it was. They were curious to see if I knew how to play the stuff they did. And I did. I had gone through this already in San Francisco, where the drummers were every color imaginable.

Here I have tried, unsuccessfully, to construct a link to Drums Along the Dupont, which can be found under “Publications.”

I ended up integrating it, although I didn’t know I was doing that at the time. I have been interviewed a half dozen times about it, and there are still videos floating around here and there with me giving my version of things. I don’t wanna say anything more about it, except that it was rough at first. It was finally accomplished, with little more than a few words, through the good grace of the late Barnett Williams, who played with Gil Scott-Heron and The Last Poets. In the park, he was regarded as a chieftain and a man of great respect. The integration process was also a lot less violent, nasty and dangerous than what black school kids went through trying to attend school.

There are those who say that I opened it up for white dilettantes to come and pound on whatever they felt like, screwing up the grooves. But I haven’t noticed any particular people of any particular color having any sort of inbred tendencies to screw up the groove. Indeed, people of all colors do it. People of all colors show up drunk, people of all colors get into endless arguments about absolutely nothing, people of all colors take endless inept solos, people of all colors mess things up. It takes constant vigilance to keep a groove going—and there is so much street in all of this that it can only be good up to a point. It’s not art, or if it is it’s around the level of graffiti or maybe even the murphy. It’s more like therapy for the city, in a city where most people work very hard and need a break from all that uptight shit all week long.

The drum circle became my church of choice, as it remains to this day. I’d played in these circumstances in other cities, notably San Francisco and New York. Sadly, there was never one in Detroit. Richard Walls opined that the idea was too primitive–“people in this town are more interested in studio effects and hitting the big time.” I never found out otherwise.

I usually show up with timbales and play straight through for about four hours. There is nothing to describe the physical feeling of locking into a groove with 30 other people for that length of time, it’s a serious high. I once described it as some sort of dopamine kicking in. And afterwards, sometimes the best part is the ride home. I transport myself and my drums on bicycle and bike trailer, and I know all the small, semi-quiet streets. The nights are warm and clear, and I ride along a series of tree-lined lanes, with no sounds but the swish of the bike tires.

This brought to mind the memoirs of James Blades, a percussionist with the London Philharmonic. He wrote that, as a lad in the 1920s, he played drums in jazz bands in a lot of the smaller towns in England. He also traveled by bike, drums and all, and he would merrily roll through places like the Cotswolds late at night, surrounded by trees, peace and quiet. It’s an excellent way to decompress after hitting frenetic grooves on a bandstand. Fifty years later, writing about his life, he still remembered that wonderful feeling. I never thought I’d be able to capture anything like that, but I’m at least approaching it.

Some guys have been spending their Sundays coming by and filming us and then posting it on YouTube. One easy Google is: drumming and dancing at Malcolm X Park

My first published piece in D.C. concerned the drum circle, and it ran in the Washington City Paper. This was probably at the last possible date that one could actually walk into a publication’s office as a total stranger and pitch an idea to an editor. This was the first time I had ever done this, and I was motivated by reading an article on hip-hop by one of the paper’s editors, a smart young lady named Alona. The piece showed an appreciation of percussion, and I figured that she would make a suitable target. I was right, and she bought it. When it ran, a young lady I knew from the neighborhood saw it, liked it, and asked me if I was interested in working for Reuters. Just like that. Not a word about my formal education, resume, references, police record, none of that. And a good thing, too.

The job was recording hearings on Capitol Hill, and through that I entered the journalistic fringe that kept me fed and sheltered for the next few years.

I also wrote, just for fun and to maintain my version of volunteering for the better good, for The Postfundamentalist Press. This was an online ‘zine published by a colleague of Ken Sitz, who had introduced me to Alfred Jarry so many years before.

Ken introduced me to a young lady whose pen name was Poppy Dixon. She was born and raised in a born-again Christian variety, and rebelled. That’s the story I got, anyway. She wrote and ran stories that cast ridicule on the Religious Right. My kind of place, I thought, reading it over. She had even used the title of Leo’s book, God is my Booking Agent, in one of her articles, seeing it online, but not knowing who either of us were at the time.

I had written a long–way too long–piece on religious misbehavior for Screw, and they didn’t want anything of that length. So I sent it to Poppy. She liked it and ran it in three consecutive issues. I would get strange fan mail from it; very serious stuff from young kids who had been victimized by some of the sleazeball holy rollers that I talked about. My aim was to fuel ridicule and get laughs, mostly, but not one response mentioned how many chuckles it had given them. They talked about how their lives had been near-destroyed by people like Billy James Hargis. I still find it unfathomable that whatever gene or glandular insufficiency that drives spiritual belief can cause people to be led into such despair.

(I’m still trying to put a link in, this time to SCANDALS IN EDEN, but still haven’t figured out the moves. Until that happy day, it can be found under “Publications.”)”

JAMIE FOSTER BROWN

When I got to D.C., I joined the Washington Independent Writers, sort of writer’s union, one that had a job bank. Thanks to Leo’s book, which was selling at a rate of one copy every fourteen months, I qualified for membership. And I was hanging out there, one afternoon, when they got a call. It was a small African-American magazine called Sister2Sister, run by an amazing woman named Jamie Foster Brown.

She was a black gossip queen, a staple on the smaller TV shows, delivered “the skinny” on various celebrities—and in Afro-America they rose and fell faster than pinball scores. Her magazine had a lot to do with black celebrity, and since I had just ghosted a book for a black celebrity, the lady turned to me and passed me the phone.

This would be a source of fun and money and friendship for the next 15 years, off and on. I wrote the stuff they asked me to; starting out with profiles of African American women who had succeeded in business. I described this chore to a female journalist pal of mine. Her reaction was one word: “Snore,” and I came to agree with that real quickly. I asked Jamie for some more challenging assignments, and she cheerfully provided some.

I met Melvin Van Peebles through her. I went to interview him at Union Station, he was about to head back to New York. We had a nice, long talk. I had heard his first LP, back in those three days I was in Los Angeles. One of the songs was called “Catch That on the Corner,” which had a strong musical hook that I can still remember. The text was about a black guy beaten blind by the cops. It was spoken, not sung, and I thought that, what with the solid musical groove and the pitch-perfect delivery of the text, it was one of the most effective poems I had ever heard. Forty years later, it remains that.

Melvin himself was a witty, personable guy that you couldn’t help liking. When he was getting on the train, the conductor addressed him as “Mister Van Peebles” at first sighting. Other people in the station did the same.

He gave me his phone number in Manhattan, asking me to call him the next time I was in town. “We could get into some serious trouble,” he laughed.

I don’t really understand why I wouldn’t want to call such a cool guy as that, but I never did.

I did a phone interview with Andrae Crouch (1942-2015), the gospel singer and absolute monster musician. We didn’t talk much about music; from the first sentence he went on about religion and how he wanted to show his thanks for the blessings that God had given him. At one point he said that if it wasn’t for the Bible, we wouldn’t have learned about democracy.

I phrased it differently, but…beg your fucking pardon?

There’s a balance you have to find, while interviewing. You want to maintain a congenial mood, but some things are too wigged-out to go unchallenged. “Democracy?” I asked. “What does the Bible say about democracy? The Bible talks about slaying Caananites and plagues of locusts and slaughtered Egyptians and –“

“Well, I meant that we wouldn’t know about what’s right in the world.”

Well, sometimes you can let these remarks through, and turn them into a joke, and make the guy look a bit foolish. But anyone that could make music like Andrae didn’t deserve that. So I went at it from another angle.

“Oh. Well, okay. Let me ask you this. If you had to choose between keeping your musical abilities and your Christian faith, which one would you—“

“Oh, my God! Are you joking? My faith! A thousand times over! No question! No contest!!” He obviously couldn’t conceive of anyone thinking any differently about such matters. In fact, he was curious that such a thought would ever occur to anyone. It struck me, although later, that putting that question to Andrae Crouch was like putting that question to Bach. Anyway, we parted friends.

“I’ll call you when I get to D.C. We gonna have a good talk. We gonna have some serious fun!”

Well, serious fun, serious trouble. They’re pretty close.

After a while of stuff like that, told Jamie that I’d rather write about movies. I actually knew something about movies, most of my higher education adventures had to do with film studies, and I’m real good at pointing out flaws in other people’s art, while minimizing those in my own. Jamie thought about that and discussed it with her husband, Lorenzo Brown, who had just made a vow to get her magazine into the bigger time.

Lorenzo was a trip. He was a professor of economics at Howard University. He had done his PhD on economics in Sweden. In Swedish. He was thoroughly capable in whatever task that came up, from editing to software adjustments to hiring and firing. He and Jamie owned a farm in Prince George’s County, and a house in the city, and they raised two sons, fine lads, both of whom now work in D.C. real estate. He was certainly the only black economist that drove a pickup truck and listened mainly to Willie Nelson.

He came up with the idea of bringing a black, female journalist named Joia Jefferson into it, and giving us a couple of pages to bring our different perspectives on either a particular film or a concept. We called it Mixed Reviews, and did it for a couple of years. I have lost the few that I thought might be worth exhibiting. The best part was the perpetual screening invitations—about three new movies a week in those days—and the occasional junket.

During one of them, just as we were about to go to the airport and wrap it all up, a freak snowstorm hit New York, grounding me and about 50 movie writers from all over the country. Disney was left with no choice but to foot the bill for another week in Central Park area hotels for all of us, while we frolicked in the four-foot snowdrifts in the East Village. Everybody, sitting in the hotel bar, ordering their fourth drink of the afternoon, would say, “Charge it to the Mouse.”

It was her magazine that gave me a spot for a piece on the hooker’s life in Trinidad.

TRINIDAD

I wasn’t playing much music at this time, just drums inna park. I was concentrating on re-inventing myself as a literary fellow, or at least someone exploited by editors instead of booking agents. I had been hired by a wire service that covered congressional hearings on Capitol Hill. It was pretty frantic during those rare times when the House and the Senate members actually showed up and held hearings, but pretty dull during the times that they were back in their districts or diddling their interns. Or on fact-finding missions in the Bahamas. So I would take some unpaid leave and explore the Caribbean as well. Considering my budget and theirs, I felt that there was little danger of running into any of them in the watering holes.

Trinidad gave me one of the few confluences of my various lifestyles. I landed in Port of Spain, Trinidad, sometime in the 1990s, with an eye toward getting better acquainted with the Island’s music. I got in late at night, landing in a beautiful airport (!), one that, with its mahogany counters and benches and human-sized architecture, reminded me of the public buildings in Burma. A taxi took me into town, through a forest of whistling frogs. According to the cabbie, they whistle at night, during the rainy season. Trinidad is apparently famous for that in froggish circles.

I found a hotel room, but 2:00 am in a strange city and country isn’t usually the best way to get to know their way of life, so I stayed inside. I turned on the TV, which is always a good way to learn bits and pieces about your new surroundings. The first channel I opened was running a Three Stooges Marathon!! All night long!!

I knew then that I was going to like the place; that the natives had attained a level of culture every bit as refined and deeply intellectual as my own.

Calypso has always been one of my favorite musical forms; both for the grooves and the lyrics. It is one of the few popular music forms that not only utilizes clever turns of phrasing and relevant content, but is dependent upon it. (I have to admit that country music is another. And, I further admit, rock and folk songs.) I had read of the cutting contests, where a few calypsonians get on stage, take subject suggestions from the audience, and proceed to sing a song about it, extemporaneously, in rhymed verse. Harold Courlander, after attending a couple of these—back in the 40s and 50s, when they still held them–wrote that afterwards, he marveled that the singers, who looked “merely like average, everyday Negroes on the street, were men of genius.” By the time I reached the islands, however, this sort of casual, semi-amplified musical poetry slam could not compete with the loud, throbbing, laser-fed SoCa that was drowning out pretty much everything else. So I spent my evenings sitting in on bongos with whatever Latin jazz band I could find.

I never thought I’d ever say anything like this, but I found the Caribbean islands to be otherwise kinda dull. It was respectably naughty, in the manner of an old copy of Esquire. The idea of a wild time was a pub crawl. I saw a couple of those in progress and found them indistinguishable from a frat house movie. I tracked down very few live music venues, even fewer dope-smoking venues.

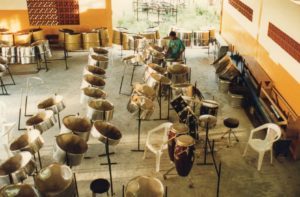

Getting ready for Carnival

Woodford Square, in Port of Spain, Trinidad’s Speaker’s Corner

The U.S.-led drug war has manifested in one of its nastiest forms there, as every government was dependent on U.S. aid money for practically everything, and scared shitless by the overbearing land of self-righteous bullies up North. So, for instance, the newspapers were bragging about the latest government plans to “deprive marijuana smokers of employment.”

It seemed as though the island governments had collectively decided to put themselves forth as a piece of America’s playground, and designed themselves to be palatable to that country’s moneyed class. And that class favored safety, smiling natives, gambling, boozing, water sports, beaches, dancing to DJs and wife-swapping. I got the impression that any natives that couldn’t fit themselves into this portrait had been gathered up in government helicopters, taken out to sea and thrown overboard.

The thought of tossing beggars out of helicopters brings to mind a short digression on that subject:

Bokassa Digression

Jean-Bedel Bokassa, ruler of the Central African Republic from 1966-1979, was such a caricature of an African tinpot dictator that one is tempted to think the whole thing was a piece of street theater. He killed thousands of his subjects for quite vague reasons, possibly just to get rid of potential competition, but that’s just dictatorship 101. In 1979, way ahead of Trump, he had hundreds of schoolchildren arrested for refusing to buy uniforms from a company owned by one of his wives. It is said that he personally supervised the massacre of 100 of the kids. He was accused of cannibalism and feeding his opponents to animals. He spent the country’s entire foreign aid package on his coronation as emperor, where he also officially proclaimed himself Best Soccer Player. And, to clean the streets for the French coronation visitors, he actually did order his soldiers to gather all the beggars and hustlers up from the streets and dump them in a river filled with crocodiles. And in a piece of idiotpolitick that shows that absurdity in Developing World government has not left us, he recently received a posthumous pardon from his country’s current leadership.

End Bokassa Digression

Trinidad has a spot, right in the middle of Port of Spain, and directly across from the president’s headquarters, called Woodford Square. It’s a kind of a Speaker’s Corner, in the manner of Hyde Park in London, where anybody can hold forth on any subject, which I found profoundly entertaining, and I took my morning coffee there every day I was in town. This alone makes Trinidad several cuts above the other islands. Then there was calypso. And then there were the steel drums, the pans. I was thinking about doing a magazine piece on pan orchestras, but after I saw how much information there was to wade through, I suddenly remembered that I was supposed to be on vacation. I bagged the idea. I went into bar to celebrate not having to research anything, and Michelle hit on me. After five minutes of conversation I realized that I could write about Caribbean hookers instead. I could research her with just a couple of interviews and produce something in a fairly relaxed manner. So The (Minimum) Wages of Sin came out of that. And what came after was kinda funny.

The CEO of the place I worked was a right-wing, born-again Christian, partial to Moral Majority politicians and “charismatic” preachers, landing somewhere to the right of J. Edgar Hoover. He had done some prison time for white-collar stuff, and had been converted to Christianity by Charles Colson himself. Nevertheless, he was a very nice guy and we got along. He wasn’t the sort to stamp his views or opinions on his employees; he appreciated good work and wasn’t afraid to pay for it. His wife, a tall patrician with a keen sense of noblesse oblige, would come in now and then, helping out here and there.

One day she asked me about my Caribbean trip, and rather than have to explain that I’d found most of the region about as exciting as a week-old mango, I just tossed her a copy of the piece I’d written. Afterwards I thought I might have made some sort of social blunder, considering Michelle’s nuts & bolts explanations of her profession—scrubbing the penis in case it’s diseased or “it takes so long to give (drunks) erections.” Then—and yes, I’m generally paranoid–I started to wonder if she would find it insulting or even some kind of actionable workplace harassment. Before you sneer, trust me, I’ve seen some leaps to unbelievable heights of subjectivity when this sort of thing gets discussed.

But there was nothing like that. Ms. B— came in the next day and told me that Michell’s story had moved her, almost to tears. She wanted to do something to help Michelle, and she had come up with a solution that I wouldn’t have considered in four million years of serious thought on the subject: Ms. B—-wanted to groom Michelle to be Port of Spain’s…Avon Lady.

Well. At first I thought it was kinda funny, the idea that Michelle could make the transition from taking on 12 men in a row to ringing a hundred doorbells a day. But then I thought, maybe Mrs. B— was on to something. Hookers, having kept the condom industry alive for years, may well be doing the same with makeup. In fact, it would seem that hookers could be great high-volume customers, considering the constant replenishing they would need to perform, and the paces they put their bodies through. Maybe Michelle’s old brothel colleagues could constitute a springboard demographic.

Ms. B– explained that there was an initial investment to be made, one that paid for the samples, personal makeup, receipt books, fragrance testing devices, and whatever other tools of the trade that no Avon Lady would dare ring doorbells without.

The nut wasn’t much, something like $300, plus a bunch of samples and instructions, and Ms. B— offered to front it. That’s when I had to step in. I liked Ms. B—-, and I didn’t want her to throw money at Michelle. Michelle was sweet and harmless, but she was also an endlessly needy hooker, with a history of buying unsuitable presents for even more unsuitable men.

“Ms. B—,” I said, “you don’t know the whole story. I left out a couple of factoids, ’cause I didn’t want to cause Michelle any legal problems. For one thing, she smokes crack whenever she can, a point in time I would define as the minute your money order gets into her hands.” Crack cocaine, in fact, is supposed to have been invented in the very Hell’s Gate housing project that she lived in. She was quite proud of this “fact” and repeated it several times, sometimes pointing to various dealers that were liming about, and blowing them kisses.

“Then, in the unlikely event that she doesn’t blow it on dope, she’ll blow it sensibly. On food, clothing, repaying debts. She’ll use it to satisfy an immediate need, a lot more urgent one than skin care cream. I think that the best you could expect from this would be a follow-up sob story and a request for another couple hundred.”

To her credit, that second scenario was good enough for Mrs. B—, and I duly shipped the money order and a sweet-smelling package to Michelle’s post office box.

I was wrong about the sob story; neither of us ever heard a word from Michelle. I remembered the last line in the piece, where Michelle worried that the next time I tried to get in touch with her, she would be dead. Maybe she was.

Mrs. B— took it in her stride, reminding me that she had been doing charitable work for years, and disappointments were just part of the game. To her, it was as important to try to help people as to succeed at it.

And it was a while before I cracked any more snotty Christian jokes.

BOOKS YET AGAIN:

Edwidge Danticat, a Haitian female writer living in New York, wrote that the mere act of reading books, under Papa Doc Duvalier, was highly suspicious, and not a few Haitians were executed for reading things that may or may not have been “subversive.” Imagine, in our information-saturated world of today, wanting to read a book so badly that you would risk your life for the chance. At this point, writers are more likely to risk their life to get you to read them.

I visited Haiti in the 1990s, and discuss it below.

The gentle reader is referred to GIMME THAT OLD TIME RELIGION, under “Publications.”

HAITI

I wrote a lot about that island in the Postfun collection, and I’ll try to avoid repetition. I remember the Miami Airport; there was some kind of warning sign from the State Department, announcing — in diplomatic language –that Haiti was considered very dangerous and anybody foolish enough to have bought a ticket should consider shredding it and that this was their last chance. Something like that, anyway.

I didn’t worry about it. I have been warned about “dangerous” places so many times that this kind of talk goes right into the same dark spot in my brain that shreds car talk and computer manuals. Also, I had already paid for a non-refundable ticket.

We had an uneventful flight to Port-au-Prince, and as we waited in line to get our passports inspected, there was a Haitian folk/jazz trio–saxophone, congas and accordion–playing, merely to welcome us. Then I saw a couple of Central Casting Tonton Macoutes–expensive sport shirts, wraparound sunglasses, hard expressions–who looked my way and started straight for me. I stood my ground, but only because there was nowhere else to go. They approached me, looked me up and down, and asked me to step aside.

I’m sure some people are asking what a Tonton Macoute is, and those who don’t know what they were should consider themselves fortunate beyond words:

After a 1958 attempted military coup, President for Life Jean-Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier formed his own praetorian guard, selecting slum thugs and giving them basically 007 status. Or at least the license to kill part. This didn’t, however, include a salary, so the wardrobe and the bar bills were their own. They simply used their life n’ death powers to shake down anyone that had anything they wanted. In the process of squeezing what they could out of the impoverished island, they killed between 30,000 and 50,000 Haitians during–and even after–Papa Doc’s reign.

I remember reading one Haitian story from Vinnie Teresa, a Boston wiseguy from the Patriarca family. He was looking into opening up a casino, like Meyer Lansky had in Cuba. He was being escorted around Port–au-Prince by the Macoutes. Some beggars came by, attracted, as beggars are, by well-fed foreigners, white men in clean clothing, and they begged, as beggars do. The Macoutes pulled out clubs, coshes, probably tire irons, and simply smashed the beggars’ heads open. Right there on the street, in the middle of the day.

Vinnie, who knew a thing or two about busting heads, was appalled. He felt that this sort of thing, like sex with your wife’s sister, is best performed in private. There was no way a country with blood running down the streets was gonna be the next Big Thing. He went back and reported to the rest of the family that the only thing they should do with Haiti was to keep the fuck out of it.

So that’s who I thought were coming for me.

By that stage of my life I had gone through hostile customs inspections so many times that I was almost always clean; it’s a rare chunk of hashish worth the risk of a smuggling rap. But my experiences, even at that, have been almost uniformly dreadful. I’ve had to strip naked, undergo probes, empty every bag I had, fend off aggressive sexual predators, and every single time I had to stifle snarls and wisecracks, pretend that they weren’t making me angry, and actually feign respect for those twerps. So, I was no stranger to being singled out in a customs line.

Here, however, they wanted me to step aside because they had come to assist an elderly gentleman who was standing behind me. They escorted him, with smiles and great courtesy, to the front of the line. I went through afterwards, also accompanied by respectful smiles.

That’s what Haitians are like. They certainly have their thugs, but otherwise, even the customs officials are rather nice chaps. In the two weeks I spent there I didn’t find a Haitian that wasn’t.

Like so many Developing World societies, however, power seems to turn even nice people into the kind that start to enjoy chopping their competition into small chunks of meat.

BOOK DIGRESSION: THE COMEDIANS, GRAHAM GREENE

I thought of The Comedians approximately 87 times a day while I was there. The Comedians is, I think, Greene’s best book, and if not the best it is certainly his most frightening. It spins a tale of life under Papa Doc Duvalier, probably the cruelest dictators in a latitude noted for plenty of them. Let’s look what he had to work with.

A couple of fun facts about Papa Doc, President for Life Jean-Francois Duvalier:

Papa Doc–he ruled from 1957 until his death in 1971–used Voudou—the island’s primary religion–quite effectively. He likened himself, in the public mind, with Baron Samedi, one of the scarier loas (gods). Samedi is the loa both of the dead and fertility. I don’t know how that’s reconciled. As with a lot of religious dogma, I can’t comprehend it. The Holy Trinity would be just one more example.

Baron Samedi generally dresses formally, in a top hat, black tail coat, dark glasses. He also wears cotton plugs in his nostrils, which is how Haitians dress a corpse for burial. He is noted for disruption, obscenity, debauchery, and is partial to tobacco and rum. Naturally, he reminded me of a lot of musicians I have known.

I’m not sure if Papa Doc was the Baron’s Stooge or the other way around, but the power he got from his voudou identity helped lock him into the palace, and he didn’t leave it until they carried him out. His government confiscated people’s landholdings, giving them to the Macoutes, who, remember, weren’t paid anything.

Although he had a legitimate medical degree and was a licensed physician, he was as superstitious as Osama bin Laden. He believed that one enemy he was chasing had turned himself into a black dog, so he had all the black dogs on the island killed.

Greene’s book took the POV of a British innkeeper, simply trying to keep his business going, surrounded by other people who wanted nothing more than the same sort of thing, and who were picked clean and ruined and/or murdered under Papa Doc’s regime. He spun a harrowing tale, and it was one of those stories that stayed with you, like malaria, for years afterwards. It became one of the finest books of the 20th century.

When Papa Doc heard about the book, he instructed his newspaper editors to run front-page stories about Graham Greene’s being arrested for child molesting, cannibalism, sodomy with underage boys, and whatever else they could think of. This, according to Greene, went on for years, even after Papa Doc died.

The book, like pretty much everything Graham Greene ever wrote, was made into a film. Incredibly, it starred Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, during their hyper-mega-super-duper star phase. It wasn’t their greatest hit–I actually don’t know if any of the movies they made together were any kind of hit–but in some ways, it wasn’t too bad.

Sitting in the bar in Olofson’s—Graham Greene’s Trianon–I made the acquaintance of a man who introduced himself as Dr. Georges Michel, who wrote Haiti’s Railroads, the only book on the subject. I’m a rail buff so we had a long talk. He told me that the Americans convinced the Haitian government to stop using train transport in 1932. As noted above, Caribbean governments seem to be quite happy with their puppet status when it comes to U.S. “suggestions.” So they let their train service go to seed, not unlike Los Angeles in the late 1940s.

Under Papa Doc, when the railroads fell in need of repair, he simply discontinued the service, letting the Macoutes sell the track metal for scrap. (The book also accuses the American soldiers, from the 1995 invasion, of doing the same thing, so I kinda wonder about some of the other claims.)

RAILROADS:

http://islandluminous.fiu.edu/part07-slide13.html

Caribbeasts, part 2: A Quick Look at Trujillo

Papa Doc—when he died a British journalist said that “few men have deserved fewer tears”—was a tinpot dictator cliché, but he was just the worst of many. The other side of his island held the Dominican Republic, run for years by another president for life, Raphael Trujillo. Trujillo proved that a Caribbean dictator can be competent, concerned about the welfare of his subjects and still satisfy his inner serial killer.

Trujillo, was cruel and murderous, but efficient. He believed in environmental protection and started bringing about nature-friendly measures in the 1930s (!). He accepted more Jews fleeing Hitler than almost anybody. According to some Dominican guys I know, including some who are old enough to remember it, Trujillo loved Merengues, the national music of his island. So far, so good. He would book bands to play at functions at his palace and insisted that the band play all night long. Without stopping. Any musicians who tried to take a break really got one–they were taken out and shot. It’s safe to say that there isn’t much of a musician’s Union in Santo Domingo.

A Dominican friend of mine once told me that his country was “overrun by Haitians,” who were fleeing either one dictator or another or just general poverty. “They are like dogs,” he said. “Running up to everyone, begging for work.” Then he put on a merengue hit, El Pique, brilliantly recorded by Johnny Ventura. It’s a song, sympathetic toward Haitians and their struggles. Johnny, it is said, came from a Haitian family.

Port-au-Prince Again

Anyway, back in Port-au-Prince, I sat in with a band called R.A.M. The band plays mizik rasin music, with both modern and traditional Haitian instruments. It featured a lot of drums, a couple of guitars, and a singer/speechmaker, who fronted, gave cues and the like. His name is Richard A. Morse, and he used to play in a punk band in Massachussets.

Rasin came about in Haiti in the 1970s. People started combining elements of traditional Haitian Voudou ceremonial and folkloric music with rock and roll. This spillover of American R & B happened elsewhere in the Caribbean; Reggae was influenced by a New Orleans clear channel radio station that transmitted the music of Fats Domino and Allen Toussaint to Trenchtown. This early, black music seeded and then drove the ideas of a lot of Haitian musicians.

RAM’s music is very political, as socially critical as it is possible to be in such a place. I understand that Richard had barely escaped a kidnapping in 1994, a couple of years before I got there.

I was lucky enough to be there under Aristide, one of the country’s better leaders. There were many Haitians against him, of course, and some of the reasoning was a bit hard to process. I met a gorgeous anti-Aristede woman, from Haiti’s upper class, at a party in D.C. She was nostalgic for Papa Doc and the Tonton Macoutes, which of course implied nostalgia for the wanton slaughter of anyone suspected of anything. “How else,” she wanted to know, “can the government step on those machismo tendencies of the average Haitian man?”

I was so stunned by this that I didn’t say anything for a while. Finally, “Well, maybe a small machismo fine? Every time a guy is seen beating his chest he gets fined 20 gourdes?”

She just gave me one of those who-let-this-peasant-inside looks and walked off. “Does this mean you’re not coming back to my place?” I asked, but way too quietly and way too late.

Well, in Haiti, and R.A.M., I had traveled, as usual, with bongos, and I asked if I could sit in the next time they played. Richard told me to show up at their rehearsal and I would be auditioned. I did and was accepted. It was great fun, and the house was packed with the young Haitian elite. Yes, even Haiti has a middle class, although razor-thin and precarious, and its children have been called the “Petionville Priveleged.” Richard said something like I would always be welcome on their stage.

A few days later I was walking around, fairly aimlessly, and I stepped into what I thought was a bar. I was wrong. It was a private home that shared a door with a bar. I started backing out, but a woman came to greet me, smiling. She said, in good French–certainly better than mine–that I was welcome, and would I like to take her daughter for the evening? Then she named a price. I wasn’t in the mood, or the market, and I’m actually never in the market for 13-year olds, which was approximately where I would have guessed her daughter was. The daughter was obviously horrified at the thought. She started pleading, “No, Maman…no, no, no…”

“Well,” I said, trying to lighten the atmosphere, “I can take a hint. Heh heh heh.” I said it in English, however, to no effect whatsoever. The lady kept insisting, the daughter kept objecting, and I, pantomiming beer-drinking, finally slipped into the bar. I said earlier that most prostitutes go into that line of work as their own reaction to dreadful economic circumstances, but, okay, some of them get a push.

Years later, writing this down, I had another thought. Maybe the whole thing was a clever act. Maybe they weren’t even mother and daughter but business partners, using that scam to break into the Wealthy Sadist market. As I keep saying, it’s a jungle out there.

Something else I noticed: in two weeks of basically wandering around the island, quite visibly white and at least relatively affluent, with the exception of the designated beggar zone by the post office, I encountered exactly one panhandler. Returning to Miami, I was hit on between the taxi and the hotel door. Twice.

I’m not sure what this says about the comparative differences between the two societies, or anything else, for that matter. I’m just sayin’.

PROPINQUITY

Michelle Rhee, the combative and much-maligned former chancellor of D.C. Schools, was sent to some Ivy League college by her tiger mom and dad. They scraped their nickels together and drove her hard to get good grades, “so she would find a rich Ivy League husband.” She did, in fact, do that, although they divorced after a few years.

But her mom and dad had the right idea. Propinquity to the future big playahz of the next generation is better than a straight-A average. I heard that, in Los Angeles, there were terrible fights over slots in the kind of stratospherically priced kindergarten that people like Barbra Streisand sent their kids to. For the same reason.

At one point I had to decide between two jobs; one headquartered in Washington, D.C.’s National Press Building and another that wasn’t. I figured that propinquity to guys that did the hiring and firing at the high sides of the news industry would be the better choice. And so it was.

BOOKS AGAIN: EMBATTLED SELVES

Ken Jacobson

Working in the National Press Building, I did meet the right kind of people, and I didn’t have to go to cocktail parties to do it. These were guys and gals who had lived overseas, tracked down stories, cross-checked, interviewed and wrote them. They had also mostly remembered what they had done. Ken Jacobson, who was writing for King Publications, took that to a very high level. He was—is—fluent in several languages, and had about 20 years working life as a reporter behind him when we met.

Toward the end of the 70s and into the 80s, Ken got the idea to write a book about people’s attempts to maintain their Jewish identities, and actually their entire identities, during the Holocaust. He was living in Europe, and had just finished working for the Associated Press. And he spoke French, German, and Dutch– the kind of languages you’d expect in Holocaust survivors–at the time. Now, he speaks a few more. He’s also gifted with a prodigious memory. Once, living in New York, he was called to jury duty, and the jurors were not allowed to take notes. Not even for the judge’s instructions, which were possibly as complicated as anything that came up during the trial. So, during deliberations, he recited the instructions back, from memory.

I found that profoundly depressing. I would be hard pressed to tell you what I did 45 minutes ago with any specificity; I have the kind of memory that treats practically everything I come across like a phone number from the Information operator. The story, somewhere above, about my encounter with a Thai hooker, which one would think shouldn’t be too easy to forget, only came back to me because I had written it down, sold it and happened upon a copy.

But use his languages and memory he did, and the result was published as Embattled Selves, a very interesting study on what I might call selective adaptability. One of his reasons for doing it was “to get people to identify with the persecuted.” He is, in fact, thinking about writing a new introduction, “focusing on the EU, national identity, and refugees and (to) put it on Amazon in Europe as an e-book.”

I thought that it brought home the personal realities of the Holocaust more effectively than a lot of the first person memoirs I’ve come across. And I have to admit, here, to being a real fan of WWII. Despite the fact that my father fought in it.

Well, he fought drunks in British dance halls. But you know….

AKWA IBOM, Squaresville

I used the above word, by the way, in a Washington Times report on Akwa Ibom, a southern state of Nigeria. I think I was writing about the young Nigerians that were not following in the ways of their ancestors, or something. I don’t even know how I got away with using 1950s American beatnik slang in a contemporary ironic fashion; it was obvious that nobody in Southern Nigeria knew what the word meant. But the local media picked up the story and copied it, practically word for word, in a local journal. And they rendered it “Squares. Ville.”

I made two trips to Akwa Ibom, Nigeria, as a writer for a Washington Times Special International Report. I ended up co-writing about ten separate reports on this project. I would spend the day interviewing guys—not one woman—who were in prominent in some way or another. I would then write up the notes, put a story outline together, and then go with K. B. and J.O, the project manager and the co-writer / computer geek, and hit the bush bars.

We think that we work hard, putting in long hours in the West. I guess we do, but none of us have been a bar musician in Nigeria, either. These guys come on around 9:00 pm and play, with minimal breaks, until about 5:00 am the next morning. And they play hard. And well. Since they have such a lot of time to fill, they can creatively stretch a song until it becomes something other than it was when they started it.

There always seemed to be a battered set of congas onstage, and I was always welcome. Especially by the conguero, who knew that he could count on a nice long break, maybe even a nap, when I showed up. Consequently, I was every drummer’s favorite Toubob.

Nigeria, however, was still Nigeria; volatile, unpredictable and often deadly. Traveling from one city to the next, we had an unmarked police car in front and another behind, guarding us against land pirates. These guys were either religious fanatics looking for hostages or simple everyday thugs looking for things to steal. They would park their car sideways and block yours, and once you stopped moving at 85 mph, they had you.

Just another reason not to drive, I muttered.

The man that recruited me for all of this was a buddy, called K. I also knew him from the National Press Building in D.C. He worked at King Publications, the same agency Ken worked for. We both smoked tobacco, and would bump into each other during smoke breaks outside. I have since given up cigarettes–giving up illegal drugs was far easier–but when I consider the particular arc in my life that my friendship with K. took, I’ll never say a bad word about the habit.

We started hanging out, until he moved over to writing and marketing international reports for the Washington Times. He was being sent all over the world, interviewing various overseas bigwigs, and pulling down a nice check. He called me and asked me if I wanted to get in on it.

I didn’t. It seemed like a natural fit, but I didn’t trust it. The Washington Times was run by and paid for followers of the late Reverend Sun Myung Moon. Their newspaper has been described—quite accurately—as part of the “Republican Attack Machine” and it endorsed every halfwit right-wing policy and candidate that Middle America could cough up. I had always considered the Reverend to be one of the more annoying “messiahs,” those who ruin lives even more pathetic than their own. I thought they took some sort of insidious control over their converts, got them to sign over all of their property, and used the money to bring lawsuits against art galleries. I don’t really know if that’s true, and a couple of card-carrying Moonies later told me that it wasn’t, but that’s what I thought. So, I declined.

Kevin called again, a few months later, with a sweetened deal, and hinting that the first trip would be to Outer Mongolia. This wouldn’t seem like a perquisite to most people, but I thought it was great. At that point I started thinking about it. Weren’t most newspapers owned by right-wing whackos? Would I turn down a chance to write for Time Magazine because Henry Luce idolized Mussolini? Didn’t a lot of great journalists cut their teeth with Hearst? In other words, adaptive psychology went to work. And this time it won. So I went for it. And this became one of the best day jobs I ever had.

I had to go through an interview process, and I was, as always, worried that my lack of formal education would be a deal-breaker. It often was. A year before, I had gone through a terrific, rollicking interview at the Library of Congress for a slot on their in-house journal. Just as I was about to leave, surrounded by warmth and smiles, one of the inquisitors suddenly stopped, saying, “Kevin, we’ve forgotten to ask you about your academic career. And you forgot to fill out where you went to college, and of course graduate school.”

“Oh, yes, so I did, so I did.” It was one of those fuck-a-duck moments. I have a difficult time lying. It’s one of my rules of life, and I can’t wiggle out of it. I’ll always remember Raymond Chandler, having Philip Marlowe assess an oddball character he had just met. “Whatever his rules were, he played by them.”

So I played by mine, screwing myself royally in the process. “Actually,” I said, “I don’t have any academic degrees at all. I’m kind of an auto-didact….?”

All the smiles and good fellowship fizzled and went straight out of the room. They quickly shifted into bureaucratismo, regretfully explaining that a master’s degree was a minimal requirement.

I’m not upset about that—although I certainly was at the time. But I’m actually proud that my government has such exacting standards. Or at least they did, this was pre-Trump. Now it’s hard to say…

Well. I was instructed to meet another member of the Times team, a supremely accomplished Ethiopian named David T–. He spoke something like six languages and had been around the world roughly as many times as I had. We set up a meeting at Ben’s Chili Bowl, a D.C. landmark eatery, black-owned since the 1950s, situated on U Street NW, which was once the city’s “Black Broadway.” Jelly Roll Morton, among quite a few others, had a jazz club on that street in the 1930s or 40s, and it was there that he was rediscovered by Alan Lomax. It was Lomax that got Jelly Roll to record his famous Library of Congress oral history of New Orleans jazz, which was described so brilliantly in They All Played Ragtime. That, in fact, is a book I would recommend to anyone interested in American music. In fact…

BOOK INTERLUDE They all played Ragtime, by Rudi Blesh, Harriet Jannis

I don’t know how many people listen to ragtime piano anymore. It had a vogue in the 1970s, when Marvin Hamlisch used the genre for the soundtrack of The Sting.

IMPORTANT STING DIGRESSION: (A note about that movie: It won an Oscar for best picture, and an Oscar for best original screenplay. But it should have been Best Picture with a Plagarized Screenplay. I don’t know why no one noticed this, or why I was the only one, but one of the very first scenes, where the con men are confronted by a crooked cop, looking for a shakedown, took the dialogue, and I mean word for word, right down to the punctuation marks, from Trick Baby, Iceberg Slim’s second book. I mean, nobody has said a word about it. Iceberg’s biographer—yes, Iceberg Slim has been immortalized in a biography by an academic fellow named Justin Gifford, in a book titled Street Poison. It was kind of a fun read, but it wasn’t a very good biography. It was casual and uneven, and when it couldn’t find a fact it simply avoided it. Like Iceberg himself, I guess. It ignored whatever story that lies behind Mama Black Widow, Iceberg’s best book of all.

Anyway, he didn’t either didn’t know or didn’t mention this Trick Baby business.

UNIMPORTANT STING DIGRESSION: That wasn’t the only instance of Sting plagarism. David W. Maurer (1906-1981), a linguistics professor, author, and expert on underworld slang sued, saying The Sting was based far too closely on his 1940 book The Big Con. They actually settled, for $300,000 1970s dollars, which would have been enough to last one until probably 2020. Dr. Maurer, however, shot himself in 1981. No one seems to know why. As I keep saying, it’s a jungle….

End Sting digression

They All Played Ragtime

Well. They All Played Ragtime, by contrast, is one of the most elegant, informative and evocative pieces of writing that I have ever come across. It is almost heartbreaking, the world they bring us to, the world where every café had a piano and “professors” could travel from country to country, sit down at one of them, and their art would be loved and understood by all. Just like a silent film. There was machine-produced music, and a lot of bars used it, but it was nothing like today, where the practice has invaded every corner of our existence, including street corners and taxis and even cyclists.

One of the more interesting things I am doing, at this writing, is an attempt to sort of replicate that world. And I’ve gotten a bar owner to give me a space to do it in. More on that below…..

Good Career Move

Well, nothing history-making came up in my interview. I showed him some clips and we just started talking about various Developing World countries that we had visited. The subject of Cairo came up.

“Don’t talk about fucking Cairo,” I said. “Without a doubt the most irritating spot on the planet. Plus, I did time in the Cairo city jail. Not much, but still….”

What had happened was, David and I had gotten on such good terms so quickly that I was talking like I was holding forth with buddies in a pub somewhere. I’m being interviewed for the most conservative newspaper since The National Review and here I am talking about my arrest record.

“You did time in the Cairo city jail??” he asked. “I did time in the Cairo city jail! And the head of the entire department, Mr. C–, did three months in the Cairo city jail!”

From then on, I was in. You never know what’s going to be a good career move.

So I did a few years at the Washington Times. Nothing I experienced working on his paper caused me to alter my original opinion of the paper or the Reverend, but that sort of thing was done at a far different pay grade than mine. Me, they left alone. I was never asked to join the church or sign anything over to them. No one put the slightest half-ounce of pressure on me, either. And I have to say that some of the most intelligent and professional people that I met there were members of the Unification Church. That would include Mr. C–, an extremely bright and personable gentleman whom I still consider to be a friend.

This, however, goes through my particular prism and merely bolsters my theory that the capacity for religious belief and basic intelligence occupy completely separate compartments in the human brain.

And, it turned out to be a whole lot of fun.

For one thing, I was under no obligation to follow any political line, under no obligation to snarl out anti-communist anti-liberal venom every third sentence, or indeed, anywhere. If a bridge collapsed in a country I was writing about, I didn’t have to automatically blame it on labor unions or premarital sex. I was writing special reports, a section run by the advertising department, and it was the only money-maker the paper had, so the formula was to avoid ideology and present basically objective stories about other countries. Nobody pressured me to write nasty things about anything. I could write pretty much whatever I wanted, and that’s what I did. I was being flown in, put up in a five-star hotel–not by the government–to capture the essence of a country.

It was great. I interviewed heads of state, taxi drivers, all kinds of governmental functionaries, hookers, juvenile delinquents, eccentrics, artists of all stripes. I circled the globe yet again, this time on someone else’s nickel, and I slept in nice hotel suites, rather than in the alley behind one. As long as one didn’t call it journalism, which I was very careful not to, it was just a glittering day job. There should be more like it.

PUBLICATIONS: “THE PEOPLE’S FOOL”

This came from a report I did on Denmark. I was there two months, and I cannot adequately describe the feeling of living, once more, in a smoothly functioning, crime-free European city. I interviewed the prime minister, who went on to head the European Union. I interviewed Marilyn Mazur, a dancer and percussionist who had played and toured with Miles Davis. She was one of the most enchanting people I have ever met. I did a piece on Laila Hansen, an Inuit filmmaker. Laila told me that Inuits–the current polite term for Eskimos–speak the same language from Alaska to Greenland. Even though they have been living in these isolated spots for thousands of years, an Inuit from one side of the continent can meet an Inuit from the other side and they can understand each other perfectly. Or actually, according to other scholars, imperfectly.

My favorite bar in Copenhagen was an Inuit hangout, actually, mostly because they didn’t have a blasting loudspeaker system churning out disagreeable rock music. They, if I remember aright, didn’t have any background music at all, which I consider the first step toward civilization. They had the sounds of seriously drunken Inuits, about half men, half women. But it wasn’t aggressive, fighting drunkeness, the sort I remember from Native bars in San Francisco. I mentioned that to Laila, and she said that fighting wasn’t their way of handling things. Their history has been fighting the elements; personality concerns must seem pretty petty after that.

I don’t know how completely true that was, but I never even heard a cross word, all those nights, in the Inuit bars.

TOILERS OF THE SEA, VICTOR HUGO

On my first overseas assignment for the Times, I was sent to the British Crown Dependency of Guernsey, one of the Channel Islands. Far closer to France than the U.K., the place is pretty much independent. The British royal family is responsible for its “good government,” and the British taxpayer is not. Not too many official aspects of modern British life have made it there; there’s no National Health Service, no nationalized industries, and even the Guernsey pound is completely their own, and not legal tender in the U.K. The only aspect of their life that London is responsible for is defense, and as the Channel Islands were the only sliver of English territory that was occupied by the Nazis, that doesn’t seem to have made much of an impact either.

Guernsey’s economy is heavily dependent on financial services. This takes in everything from banking to health insurance for ex-pats working in the Middle East. And it seems to be succeeding. When I was there, the island had an unemployment rate of 0.01 percent, simply astonishing for an English-speaking community.

As to the Nazi times, Guernsey maintains an Occupation Museum, and it’s one of the stronger tourist attractions. I wrote the following piece about it:

PUBLICATIONS: OCCUPATION STORY HERE

Guernsey struck me as being about 30 years behind the U.K. In some of the better ways, the architecture was almost exclusively pre-brutalist, brick, two to three stories, looking somewhat hand-built. There was only one glass & steel box on the entire island. The jukebox in the pub at the Duke of Richmond Hotel, where I stayed, still played the songs of Their Finest Hour; old stars like Vera Lynn and Ivor Novello, and wartime ditties like “We’re Gonna Hang out our Washing on the Siegfried Line.”

In an example of the worst ways, the local police chief informed me, with a cold sneer, that “cannabis smugglers are being severely dealt with.” He was a veteran cop in a place without any criminals, and was probably feeling useless. So he tried to piss me off, most likely to create some kind of conflict, upon which his paycheck depended, in fact. He did, of course, piss me off, but I kept my personality in a severe neutral throughout the interview. This is how I talk to cops anyway, anytime, anywhere…

The economic fortunes of the island have been kind of interesting. The Guernsey cows, of course, are well known, especially when one considers that there aren’t actually that many of them, and they have contributed very little to the island’s riches. They are dairy, rather than beef cows, and they apparently got their reputation from the high quality of their milk.

The island’s economy did a lot better with tomatoes, or at least for a while. The “Guernsey Tom” was the most profitable agricultural product that Guernsey ever grew. Old timers, when I was there, could still remember roads lined with of tomato lorries, heading for the docks and England, as far as the eye could see. Their tom was as well known as the Florida grapefruit. But Britain’s early-60s entry into the European Common Market, and the inevitable bumping up against growers in lower-rent places like Portugal and Spain, pretty much squashed the Guernsey Tom. When I got there the island was dotted with abandoned, neglected greenhouses.

Tourism was big, for a while, and it’s still healthy. But it used to be massive. British rail employees could travel, for free, with their families, to the end of any line, and of course some “railroad” lines connected with ferries. They stayed cheaply in guest houses that the tomato farmers rented out, and relaxed in the incongruity of stone Norman huts and palm trees. But again, the price of plane tickets to places like Spain and Portugal and Greece fell, and members of the “Bucket and Spade Brigade” found they could sun themselves under far cheaper skies. Globalization, basically, in an earlier iteration.

After that kind of one-two punch, the wise men on the island had the idea to shift over to attracting financial services firms. In this they succeeded wildly, and by the time I got there–1999—they had changed the island’s prime directive and sensibilities to the point that fresh copies of the Financial Times were mounted, every day, on the lavatory walls of the pubs.

Sir John Coward—a retired military man—was governor general. He was a marvelous English gentleman, one who had, despite his last name, risen to the rank of admiral in the British Navy. He and his wife invited me for dinner the second or third night I had arrived. It was his way of checking me out, to see if I was credible—the Times’ reputation as a whacko Moonie publication gets around—and to see if he would recommend that his – well, subjects – should be advised to speak with me.

Sir John and Lady Diana had a piano in their residence, and I established my Anglophile credentials by playing things like “A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square.” Later, Sir John showed me one of the new British pound coins, which looked so cheap and shoddy that I wouldn’t have traded a quarter for one.

“That’s the new pound?” I asked. “It looks like something we’d expect from Clement Attlee.”

There were several toffs in the room, and everyone shut up, astonished. Sir John looked at me and asked, “You actually know who Clement Attlee was?”

I nodded. The British Council Library in Vienna, again. Along with Dickens and Priestly and Sgt. Beef I had read a whole lot of British historians. Clement Attlee succeeded Sir Winston Churchill as prime minister, almost before WWII was over. He headed the Labour Party, and brought in all the semi-socialist reforms that the Brits had been hungering for since the turn of the century. He nationalized the coal, gas and electricity industries and brought in socialized medicine.

I personally think that he was a great man, and utterly underappreciated, but he had none of the class and wit and style of a proper British prime minister, and it gave people the impression that he wasn’t much. Minimizing class differences is all well and good, but there’s a certain sacrifice of class itself that comes along with it. Churchill called him– unfairly, but that was Winnie– “a modest little man with much to be modest about.”

So, fair or not, the idea that Clement Attlee would create a modest little pound coin was logical, and it went down well. I seemed to be someone who had a vague idea of what he would be writing about. From that moment I was in. There were some well-placed phone calls, and I had a nice interview with everyone I wanted to speak with. And with some, like the police chief, that I didn’t.

So—I swear I’m getting to the point—on this island of Guernsey, there is a cottage-like house that is maintained by the government of France. It was Victor Hugo’s place of exile for 15 years. He had run from France after calling Prince Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte III—the Bonapartes in France were like the Gandhis in India and the Corleones in Hollywood—a couple of bad names, including “traitor.”

The house, a rustic cottage, really, has the writing table that Hugo used to write Les Miserables. In those days, the tables were higher and writers stood as they wrote. This practice, of course, is returning, mostly due to fear of sciatica. Hugo’s tables were all over this house, as he built them himself, out of discarded doors. I had, some years earlier, visited his apartment in Paris, also maintained by the French taxpayer. It’s quite different in style, with red silk wallpaper and gold trim. And although I hate pretense and fancy décor, I felt immediately comfortable there. This was somehow elegant without raising one’s nose.

I’ve read a lot of Hugo’s work. It’s great writing, the stories move along beautifully, and the points get made. I could see a 19th century reader blessing M. Hugo for providing so many evenings of entertainment. I should also say that his stuff is real serious. He was one of the prime movers of the 19th century Romantic movement, where a daily dose of cold, cruel injustice and hideous tragedy was as natural and inevitable as the outhouse in back. And yet, in every one of his books, there’s a tiny slice of comic relief. It could have been because the weight of all that misery was getting him down. And they’re howlers.

The only one I can remember well enough to repeat is from Les Miserables, when Jean Valjean is attacked in an alley. It’s just a common mugging, and Jean manages to subdue the ruffian, and throws him against a wall.

“Why don’t you work?” he yells, quite upset with this specimen.

“It is fatiguing,” the ruffian replies.

Coming after chapters of sadness and fright gives it quite a stage to appear on.

The Toilers of the Sea

So, anyway, the book concerns a ferry that went down in the Channel during the 19th century. The captain purposely scuttles the ship, to somehow position himself to search for a cache of treasure that had been lost there. And he was doing this because the fair Deruchette, a lovely maiden from the island, had made a public promise to marry the man who recovered it. Don’t snicker. This was the romantic era. For all we know, people may very well have done things like that.

Gilliat, a typical young strong and righteous Hugo hero, is, of course, deeply in love with the fair Deruchette, and vows to get the treasure first. So he goes to the wreckage of the ferry, scuttled on rocks—some of the seabed in the Channel isn’t very deep. There’s a passage in The Wreck of the Mary Deare—the book, I don’t remember the movie very well—where some guys find certain spots where the water only comes up to their waists.

Yes, well, Gilliat finds some of the vital parts to make a dredge, and those he can’t find he builds, by creating his own blacksmith’s shop in a cave, just above the water level. Hugo waxes eloquently and endlessly about the nuts & bolts of the smithy’s trade, not at all unlike Herman Melville describing whale-dismemberment. I got the impression that if I wanted to go into blacksmithing—and considering the projected longevity of the planet’s current professions, why the hell not?—that book would be all I needed to set up shop.

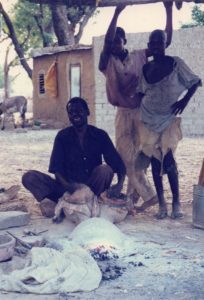

Blacksmiths, Burkina Faso, 1989. It looks like he’s playing tablas, but he’s actually pumping air through the small bellows.

Like most people, I don’t have that many pictures of primitive blacksmith equipment. These blacksmiths in Burkina Faso are about as close as I could get. They are utilizing equipment that is probably very similar to the stuff Gilliat created.

I remember one passage, where Gilliat is resting after an hours-long, difficult, exhausting session with water and heavy metal. He suddenly sits up, thinking, “What if Deruchette could see me lazing about??” Then he pulled himself up and resumed his toil, the sweet smile of his true love in his mind’s eye.

And I did say it was the Romantic period.

I found the romantic aspects of Hugo to be so far removed from my own sensibilities that I had no trouble at all with them. They were believable because they concerned people that were so different from today’s folk that pretty much anything would be believable. And so I loved the book, and consider myself privileged beyond words to have been sent, in the process of earning my living, to visit the spot that inspired it.

MORE BOOKS, OPIATE NOVELS

Like most literate people, I have been addicted to detective novels—easy reads–for decades. And it wasn’t just The Golden Age of British Crime novels. I’m always reading one, whether British, American, or Scandinavian. I’ve always got four books going, for that matter, one for breakfast, one for early evening, a pocketbook for the subway, and the detective novel for bedtime.

I’m not much for the cozies, with an amateur in an idyllic English village running rings around Scotland Yard. I like to alternate between something British/Literary and American/Noir. One of my favorites, an inclination I share with millions of others, is Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe. Nothing pulls me out of whatever wretched reality I’m going through like Nero, Archie, Fritz and all those rich Manhattanites that pay for their upkeep.

I’m a firm believer in mental R & R, and opiate novels are what I use. Other people—brainy coves—aim higher. Like Jeeves, they prefer to relax with an improving book. Jeeves was partial to Spinoza. Winston Churchill enjoyed people like Isaiah Berlin.

ISAIAH BERLIN DIGRESSION

Isaiah Berlin was a fellow at All Souls College, at Oxford, and taught, among other things, Social and Political Theory. He translated Turgenev from Russian into English. His academic achievements brought him the Erasmus, Lippincout and Agnelli Prizes. He was president of the Aristotelian Society. He founded an entire college in Oxford, Wolfson College, and served as its first president. Brainy cove, as I said.

Professor Berlin was decidedly a highbrow; in fact, he was the personification of a highbrow. Pictures of him reveal a huge, bald forehead, doubtless housing an oversized brain.

Here’s a sample of his stuff, from an essay entitled A Sense of Reality:

“Something was needed to discover historical laws, but as the laws of biology had differed from the laws of chemistry, not merely in applying to a different subject-matter but in being in principle other kinds of laws, so history–for Hegel the evolution of the spirit, for Saint-Simon or Marx the development of social relations, for Spengler or Toynbee (the last voices of the nineteenth century) the development of cultures, less or more isolable ways of life–obeyed laws of its own; laws which took account of the specific behavior of nations or classes or social groups and of individuals which belonged to them, without reducing these (or believing that they should or could be reduced) to the behavior of particles of matter in space, which was represented, justly or not, as the eighteenth-century-mechanistic ideal of all explanation.”

Well, as I said, a brainy fellow. But the more I look at his writing the more I think that I should probably aim a bit lower in my choice of entertainment. I’ve probably got more in common with Mickey Spillane.

(Sneaky, two-timing dame walks in on Mike Hammer, who has just shot up a buncha guys, see?

“How, could you do such a thing??” she cried.

Mike Hammer looked her right in the kisser. “It was easy.” )

Okay, I’m not really a Spillane fan. I’ve only read one of his books–when I was 12–and found it to be so awful and stupid that I couldn’t put it down. There’s probably a name for this syndrome, but I’ve always been afraid to look it up.

Now, as to Mr. Berlin, Prime Minister Churchill found his reports from the British embassy in America, during WWII, a source of pure delight. Churchill had one of the most liberally gifted intellects of the 20th century, and big brains tend to spot each other. Mister Berlin’s reports came to be read with the greatest of respect. One of Sir Winston’s biographers, Robert Lewis Taylor, described them as “polished models of careful research and both precise and witty analysis.” Right up Winnie’s street, one might say.

One day in 1942 or so, Prime Minister Churchill was going through his daily reports, and he noticed that one Mister I. Berlin was arriving from New York City. So when he saw the name on the shipping manifest, meaning that he was disembarking that day from a boat out of New York, he called to his staff, “I must have lunch with that fellow today!”

Mr. Berlin, pleased and surprised, came to Number 10. “You have written some wonderful things,” Winston told him. “I have admired them greatly. Now tell me, of all that you have written, which one do you think was the best?”

Berlin thought about it, and answered. “I hardly know, but I guess I would say, Alexander’s Ragtime Band.”

Yes, it was Irving Berlin, composer of Alexander’s Ragtime Band, Cheek to Cheek, White Christmas, You Can’t Get a Man with a Gun, and quite a lot of other hit songs describing things he knew practically nothing about.

Churchill, befuddled, went out, asked his secretary who he was having lunch with. When he learned the truth, he went back in and they had a fine chat about the theater.

END ISAIAH, WINNIE DIGRESSION

Returning to Rex Stout, I read a few of his other works, which I found adequate and even quite good in spots. But, like Conan Doyle, his most famous creation shone so much brighter than his others that comparing them simply shows up their inadequacies.