LOS ANGELES JUNE 1969—JUNE 1969

A Way of Life, Gone with the Wind Instruments

The unpleasant visuals of Detroit finally sent me flying to California. I had been hearing and reading such wonderful things about San Francisco that I had pretty much decided that that’s where I wanted to be. A friend of mine, Lynn Mechanic, had moved to Los Angeles, and invited me out for a short stay. I regarded that as enough incentive to leave.

I hated Los Angeles practically on sight, an attitude that has mellowed only slightly over the years. Heading straight to Sunset Strip, the first people I saw were aggressive Jesus Freaks. Great heaving mobs of them. I had never heard of this phenomenon, in Detroit they would have been laughed–or driven–out of town. Here they found fertile soil; they were multiplying, establishing colonies.

They were ex-street people, runaways, who had lived on the street for a month or so and apparently found out that there were worse forms of oppression than having to clean up their rooms and get haircuts. They were then scooped up by Christian scouts who worked as “fishermen,” tracking down aimless, homeless and indeed pointless street kids and offering them food and a flop. In return, the kids had to accept total submission to whichever Christian offshoot their particular “savior” went for, and go back out on the street to bring more converts. They would descend on the Strip in groups of dozens, in an unconscious parody of an emphatic, muscular Christianity, and start snarling at the unconverted—especially the stoned unconverted–circling them and chanting that they were going to burn in a fiery pit. Talk about a buzz-kill.

It happened to me, but I thought that they were kidding, so I just laughed along. Only later in the day did I realize that they actually meant it. I found that to be so incomprehensible that I just put it out of my mind, but it set a tone for my impressions of the city.

Those were not all that good. I felt immediately a sense of excessive girth to the place. It was spread out way over a huge area, and not of any sort of density. Istanbul also seems endless, but it’s built up, tightly packed. It’s a matter of taste, but I prefer that. And then, although I generally enjoy wigged-out characters on the street, it will be remembered that the most noticeable—and numerous–street eccentrics were howling for Jesus.

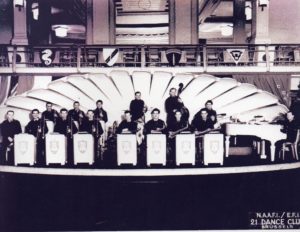

It was funny, but my father had hated Los Angeles as well. He was there briefly after WWII, looking for big band work. He didn’t get any, although I can’t really see this as being L.A.’s fault. It was 1946 and there were about six million demobilized veterans looking for work as well. And the country’s musical tastes were changing; people had had enough of big bands.

Big bands had been the staple of the musical economy, and when they went out of favor, a whole lot of musicians had to learn how to do something else. And they weren’t happy about it. Nor were they necessarily any good at it. So, basically, a way of life was gone with the wind instruments. My father told me that big band musicians were earning $200.00 a week during the Depression, when accountants were making $30.00. It sounds unbelievable but it seems to be true. But WWII had done something to the popularity of the big band sound. Perhaps there had been just too much of it, blaring out patriotic shuffles all over the place. Perhaps audiences had discovered that they could dance to records and save themselves a cover charge. My own theory is that the big bands just got too white, their sound got ever sweeter and more commercial and they lost their edge. (There are some horrific examples of what commercially- minded white bandleaders could do to jazz out there. Just listen to Sammy Kaye sometime.) With this stuff going on, rhythm & blues, smaller combos and the production of a lighter, cleaner sound, and people like Louis Jordan, were a lot more exciting. And this of course led to rock n’ roll, which changed the world.

There wasn’t much use for a trumpet in this new world. So my father found himself demobilized and out of work. He and my mother, recently married, lived in a trailer park somewhere in Los Angeles. It was filled with Okies, they were miserable there, and actually it’s quite possible that my early dislike of Southerners was genetic.

The RCAF Streamliners, WWII, Belgium. My father, on trumpet, third from left, back row.

WORLD WAR 2 DIGRESSION HERE

Speaking of my father brings me to WWII, the defining adventure of his generation.

As a baby boomer, my first thoughts on WWII were, of course, unworthy of my parents’ accomplishment. That generation had gone up against the foulest conqueror since Agememnon and smashed him into roadkill. They had saved us—or at least those of us that would have been allowed to live–from growing up in a world of standardized white people, without Jews, gays, blacks, jazz and a certain degree of codified tolerance. And, with the pre-programmed ingratitude of youth, all we could say about it was, big fuckin’ deal, ya know? My father—hell, everybody’s father—held sway with wartime stories, and we found them about as interesting and relevant as the zoning regulations of Winnepeg. It wasn’t until I was in my early twenties, when I read The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, William Shirer’s masterful history of that time, that I realized, in my vocabulary of the time, that hey, some bad-ass shit went down.

William Shirer

William Shirer was a reporter for the European edition of the Chicago Tribune, based in Paris, during the 1920s. He witnessed and interviewed and wrote about a whole lot of history. In fact he was my exact opposite; history came to him. He came upon history and historical figures, and he had an outlet to tell their stories. He met people like James Thurber, Gandhi, and Isadora Duncan, all in the course of earning a living. Even when he took a vacation, traveling to Spain in the 1930s, his next-door neighbor was Andres Segovia.

He was there at the dawn of radio news broadcasts, and was tapped by his friend Edward R. Murrow to represent CBS in Berlin, after Hitler took over. He was gifted in languages, and ended up translating Hitler’s speeches—in real time – for radio audiences in the United States. He only left Berlin when Hitler, acting upon the same sort of idiot self-worship that led him to attack Russia, declared war on the U.S.

After the war, some of Shirer’s connections in the State Department told him that the archives of the Third Reich—say what you will about Germans, but they sure know how to keep records—would be put on view for a short time, and would he like to photocopy anything?

Shirer knew a story when he saw it and did just that. He copied everything he could, an incredibly tedious process in the mid-1950s. There were 60,000 files from the Navy alone, and the files from the German Foreign Office weighed 485 tons. To this he had to add his own coverage, and the endless press handouts at the Nuremberg trials.

Then he mashed it up with his own experiences in Nazi Germany, his encounters with Nazi censors, Nazi bureaucrats, Nazi leaders, Nazi pub owners, Nazi tramcar conductors and Nazis everywhere you shook a stick. That book was the result of all that. He opened with the Santayana quote, “Those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it.”

I was in Paris, on my first overseas trip, and I enjoyed, like everyone else, the Bouquinistes, the booksellers on the Left Bank. I didn’t know what a profound tradition they were upholding—they started in the 17th century and they have brought delight to millions ever since. One fellow, a 19th century bibliophile, bequeathed 1,000 francs for them all to have a “jolly banquet,” his way of showing his appreciation for their existence.

I didn’t know any of this, but I thought that people selling high-class, low volume books, many of them gilded or bound in multicolored leather, deserved some of my business.

What I did buy, however, was a paperback Rise and Fall. It got me through train and bus rides in about five countries, and explained that world to me.

There have, of course, been uncountable books about that time, written before and after Shirer’s—Hitler was a monster of evil, certainly, but he was the best thing to happen to the publishing industry since The Joy of Cooking—and I suggest that this book is the place to start.

END WW2 DIGRESSION

Back to my father. He left Los Angeles, never to return, just before I was born. This saved me from having to enter “Pink Flamingo Gardens” under the “place of birth” category on job applications. I hit L.A. some 20-odd years later and, for utterly different reasons, had exactly the same reaction. It was bloated, car-dependant and smoggy. There are great, brilliant people living there, and I love movies, but I couldn’t stand the place. I hated every smog-filled minute of it. And I was staying in Laurel Canyon. Eric Burdon was staying across the street. Carole King was about a block away. What if I’d been in Watts?

I left after three days, taking a Greyhound to San Francisco.

Years later, I returned to interview a Stooge.

LARRY, MOE AND KEVIN

I promised that I wouldn’t go around name-dropping, but I did interview Larry Fine (Feinberg), “The Stooge in the Middle,” a couple of months before he died. He was living in this wonderful old actors’ home in L.A. It was a place for recognized but broke thespians to live out their puff in relative comfort, financed by far more recognized thesps like, I have been told, Barbra Streisand. It was in a garden spot, with a lot of palm trees and paths of greenery, and no cars. Everybody had their own room, and there was a human-sized electric train that looped between the rooms and the main buildings, which had doctors, nurses, recreation rooms and a big dining hall. Larry and I took it to lunch. It was full of old vaudevillians, singing songs that they had done at the Pantages Theatres in the 1920s. Larry joined in, correcting one old hoofer who kept insisting that it was really Sweet Caroline instead of Sweet Adeline. The women, mostly in their 70s and 80s, were bedecked, perfumed and bejeweled, exactly as they were when they’d celebrated Lindbergh’s flight across the Atlantic. The men wore ascots, rhinestone tie-tacks, in the manner of an early Fred Astaire. Larry, by dint of being close to a household name–in some households, anyway–seemed to be well up in the pecking order amongst his peers.

I repeat: No cars. No. Cars. Plus rent-free rooms, free meals and the company of one’s peers. I wanted to move in.

I wasn’t really a journalist at the time; I just had a comedy show on a San Francisco public radio station. I wanted to see if I could record Larry saying something–pretty much anything–nice about it. If not that, just anything at all. “Hi, this is Larry Fine of the Three Stooges and Kevin is a swell guy and he paid me a visit,” would have done just as well. He wasn’t interested, however. Moe was in the middle of some sort of litigation and had just cautioned him about making any public statements. If he’d had, why, Moe woulda knocked him onna head widda anvil.

He was glad to talk, off the record, about the old days, however, and he gave me a few insightful remarks on the nuts and bolts of Stoogedom. For instance, Emil Sitka, one of the recurring supporting players in Stoogistan, had something like nine children, and any day that Central Casting didn’t call he would go to the farmer’s market and look for day work loading trucks.

Larry made pretty good money as a Stooge, but he was a bit of a compulsive gambler, and spent every off-screen moment at the racetracks, which I guess is where most of his money ended up. By the time I met him he had had three serious strokes, and he was in a wheelchair. The walls of his room were full of cards and sketches from young admirers everywhere. I asked him about his memoirs, and he got quite upset; apparently he had had them ghosted in the 50s and the ghost kept all the money from the deal. I almost said that, Gosh, ghosts are usually known for pointing out a hidden treasure of gold coins in the attic somewhere. Ha ha. But he didn’t look like he would have found that amusing.

About 10 years later, Bob Davis, a San Francisco composer, writer and friend of mine was working at Last Gasp Publications. There, he edited the memoirs of Larry’s brother, who was a window dresser in Philadelphia. It was called Larry: The Stooge in the Middle, and it contained the following factoid:

Before he was born, a seer had told his mother, “You will have a son, and he will be known to all the world.”

True story? Genuine prophecy or boilerplate prediction? Who knows?

Comments

Leave a Reply

*

Be the first to comment.