SAN FRANCISCO 1969-1979

As the bus was crossing the Bay Bridge, I saw visions of what SF was going to look like. Nancy Walls had gone there a year before, called me up, and gushed that it was the most beautiful city in the world. As she was saying this, I could suddenly see it. I could see twilight in San Francisco in my mind’s eye. I was looking at what turned out to be Larkin Street, heading toward the Tenderloin. And when I got there physically I saw that my mind’s eye had been pretty accurate.

Henry Miller wrote about this sort of vision. He said, before he had ever visited Paris, a friend of his was talking about it. All at once, he started seeing street corners that he would visit, even hang out on. And when he got there, those same streets were there, waiting for him.

I found a few of my usual low-level jobs and slowly settled in. I attended San Francisco City College for a couple of semesters, dropping out with an undistinguished record and rounding off my “college years” a mere 31 credits short of graduation.

I don’t know why I’ve always been such a lousy student. I think being educated is a wonderful thing, but I just can’t seem to put that into personal practice. I once had a girlfriend who had a master’s from Yale. She knew all sorts of things I would have really liked to know, from Latin phrases and homilies to the melody of everybody’s favorite movement in Faure’s Requiem. But even if I’d had a similar chance, I would have blown it. I seem to have an inborn resistance to being lectured to, and I zone out in the time it takes to say capax imperii nisi imperasset. I’m sure there’s some sort of equally Latin-sounding name for my syndrome, and I suppose I might have even learned what it was. If I hadn’t, of course, dropped out of school.

I spent my spare exploring the city, writing, and eventually playing music. I naturally gravitated to the arts scene, which is, in that town, about half the population. Or so it seemed to me.

I loved San Francisco, and I still do, but by now it has gotten so expensive and upper middle-class that the struggling artists are moving to Oakland and beyond. The street loonies are thinning out, stumbling over to different municipalities, which I think is a violation of the city’s prime directive.

Legend has it that San Francisco was built on a mountain that the old Oakland Indians believed to be full of unusually evil spirits, and for centuries they steered well clear of it, thinking that if they colonized that mountain, the whole tribe would go crazy. It took the white man, with his inbred insensitivity toward astral forces, to try and construct a real town on such an unreal foundation. But they built it, named it after one of history’s odder heroes, and it’s been pulling in the misfits ever since.

When I was there, the misfits were a respected minority group, much like the Chinese, and almost as numerous. It was a rare day indeed to walk down Market Street without something weird going on. I mean, most cities have them, but in SF it was a lot larger. Misfits from every tight-ass community on the planet used it almost as a wildlife sanctuary. This was one of the reasons rents were so high, even then. But, even at that, I wouldn’t consider any of my encounters with the street crazies worth remembering, much less writing about.

I didn’t have a lot of money upon arrival, and I moved into a place called the Pontiac Hotel, on 6th and Mission, which was then skid row. I stayed there for about half a year. Its front was used as a place of interest in the The Laughing Policeman. This 1973 movie starred Walter Matthau and Bruce Dern, and was directed by Stuart Rosenberg.

QUICK BOOK RECOMMENDATION: ONLY YOU, DICK DARING

Mr. Rosenberg got roasted, and not with the good-natured kidding we associate with Dean Martin, in Merle Miller’s wonderful book about writing for television, Only You, Dick Daring. This is a book that should be required reading for anyone thinking about a career in the arts. Any aspect of the arts at all.

This 1963 book, co-written by Evan Rhodes, followed the true adventures and ups and downs of the novelist Merle Miller, after he was tapped to write a television pilot for then-star Jackie Cooper and perpetual star Barbara Stanwyck. Coated in self-deprecating humor, it’s an endless whirl of eccentric behavior, broken promises, wisecracks, and the ever-present instant treachery that makes up those who inhabit that particular peak in life. And it’s always funny. This is not easy to do.

It became a best-seller, but there was never a thought of making a movie out of it. Too many famous and powerful people were mentioned, by name, and not in a flattering light.

END QUICK BOOK DIGRESSION: ONLY YOU DICK DARING

We must now return, regrettably, to our spot much, much lower on the economic scale, at the Skid Row Hotel…

Nobody bothered me until one night when I walked into the middle of a domestic argument. Basically, some guy was beating his girlfriend, in the hallway, up and I happened to walk nearby. The woman ran behind me and hid. I had barely voiced, “Er, what…?” when I was suddenly lifted into the air and thrown across the hall. I was suddenly in a wrestling match; Gorgeous George couldn’t have done it better.

“Er…what….?” I said again, lying in a heap on the floor. The guy who threw me, all six and a half feet of him, was holding a knife to my throat.

“Keep da fuck outa my bidness, motherfuckah! Dis ain’t yo bidness! You got dat?? Don’tchew nevah get between no man and no woman!! You GOT DAT??”

I suppose I could have pointed out that this had been his woman’s idea, but I decided not to. That might make him angry with her, I thought, and I certainly wouldn’t want that. Then I thought that that was pretty funny, too, at least under the circumstances.

I can’t help it. Wisecracks, especially ill-timed, inappropriate wisecracks, just come bubbling up, unbidden. Another time, in another city, I had gone into a bodega for cigarettes and got assaulted by two ex-cons who were hanging around the door, mean drunk at 3:00 in the afternoon. Instead of “Ouch!” as I fell to the ground, all I could say was, Damn, those cigarettes really are bad for your health.

Back on Skid Row, I was fortunately too shaken up to actually give voice to the wisecracks. I simply nodded my head, indicating that he had won this round, and would quite likely triumph in a rematch. And I did mention, in the Detroit chapter, how no incident in my life would have turned out better if I’d had a gun at the time, and this is actually an example of it. If I’d been strapped when he tossed me across the room, I might have shot him. And, since I was an unemployed SRO occupant, I probably would have done some time for it, as well. Or, the gun could have fallen on the floor as I flew through the air, giving him the chance to further express his displeasure.

As it happened, however, he accepted my nod as the end of the matter, and that was that. People that spend a lot of time together, having nothing to do but get drunk and fuck and worry about every nickel are bound to explode now and then. And I thought it would be wise to leave their community before it happened again. And it would. He had already seen what a troublemaker I was…

Lynn Mechanic came up from L.A., and we moved into an apartment, as roommates, in Haight Ashbury. And this was not your older brother’s Haight Ashbury.

The Haight, as it was universally known, was, in 1969, well past the flower power stage. It was going through a very rough post-groovy phase, which happens to pretty much every “hip” neighborhood. An Esquire Magazine piece at the time called it “a case of terminal euphoria.” The Haight at this time was a sitting duck for every jive-ass thug the country could produce. There were nightly incursions by young jitterbugs from the Fillmore District, which was unfortunately one neighborhood away. They went wilding, and you can’t really beat up on 12-year olds. You just can’t. You want to, but they’re so young you automatically pull your punches. At which point they see their chance.

There were a whole lot of ex-cons, who had grown out their hair, attracted by the thought of free love, dope and a population of post-“hippie” misfits who didn’t like to report things to the cops. Charles Manson, of course, is the most famous example of this type. The cops themselves were perfectly hostile, and were in fact behaving like an occupying army. They were far more interested in busting you for weed than anything else. Rapists were running wild; every woman I met had been pulled off the street and raped at least once. Once, a young lady I was romantically involved with was held over at an appointment until after dark. I had no phone, but it was only a block away. She, no fool, just stayed there, not walking alone down that single block of Haight Street for anything in the world. And I divined that, automatically thinking that, oh, it’s dark outside and she’d have to walk an entire block by herself so she’s probably sitting in the waiting room hoping that I’ll figure this out and show up. And she was. And, fortunately, I did.

In the excellent Season of the Witch, which chronicles San Francisco life from the 1960s onward, David Talbot writes about this period. One point caught my eye. He writes that that by 1970, “heroin dealers still roamed the neighborhood as if they owned it.” I don’t remember this at all. In fact, being fresh from Detroit and still fond of an occasional snort, I went all over the Haight one day, trying to score some smack. Wrong neighborhood. The marijuana and LSD dealers acted as though I wanted to buy a boy for an upcoming human sacrifice. It took me four hours to find a guy who dealt in jones, and he wanted to see ID! Really. That, in fact, marked the end of my adventures with opiates. In Detroit, there were dope houses all over, and they guys inside were friendly and accommodating, once you got past their weaponry at the door. In the Haight the market demand was elsewhere, so heroin was a niche product, with all the bother and added expense that that implies.

Mr. Talbot also writes of the Good Earth Commune, and how influential it was. Really? Maybe it was, but I’d barely heard of it, in the three years that I lived there. History seems quite subjective, after all. It could be the Roshomon Syndrome. Or, apparently what I was looking for was not what posterity would consider important…

Music

Here’s a nice quote: “I have written and printed probably 10,000,000 words of English, and continue to this day to pour out more and more. It has wrung from others, some of them my superiors, probably a million words of notice, part of it pro, but most of it con….and I have never lacked hearers for my ballyhoo. But all the same I shall die an inarticulate man, for my best ideas have beset me in a language I know only vaguely and speak only as a child.

H.L. Mencken, and the language he was referring to was music…

It took me a few years to get stable enough in my new city to start thinking about playing music again. And there was also the fact that the music around me, Haight-Ashbury music, was so utterly uninspiring. It may have been good within its genre, but I was outgrowing it. The sound and rhythms of rock started to bore me. I was more of a jazz fan, but, what with the fusion craze and its own acceptance of shrieking electric guitars, that was also starting to get on my nerves. I was groping around, looking for something I liked, something truly odd and original. Fortunately, San Francisco, like New York, had about thirty or forty other odd strains.

The FREE MUSIC SCENE sprouted there, and I was an eager member of that tiny community. I spent several years playing–for free–in whatever venue would have me. Even at those prices, very few did.

My brother—the gifted musician—for the longest time, followed me to whatever city I was living in and then we would form a band of some sort. In San Francisco it was Ubu, based on Alfred Jarry’s character, and the theater of the absurd. We wore costumes, performed small pieces of sci-fi theatre, and played atonally and spontaneously. Just another San Francisco band, really. Frank French—a musical prodigy who was giving Beethoven recitals from the age of 12–joined us, along with a couple of neo-modernist third stream composers. As I said, just another band in a city where a good percentage of the cabbies held degrees in philosophy. It brought back a great line in a movie—I can’t remember the title—about making it in Hollywood. The hero, an aspiring film director, with several degrees in his field, is applying for a day job in a Rodeo Drive bistro. “You’re a director?” the head waiter asks. “How nice. Our busboy’s a director.”

DIGRESSION: ALFRED JARRY

One of my oldest and finest friends is a man named Ken Sitz, whom I met in San Francisco. He moved to New York in the 1980s and involved himself in the punk rock scene there, managing bands like The Dead Boys and Konk. I really liked Konk, simply because they used congas, and they didn’t seem to take things too seriously. The Dead Boys, originally from Cleveland, were known for the LP Young, Loud and Snotty, which kind of summed up the contemporary punk attitude.

One wasn’t supposed to be particularly good on one’s instrument—that would be like putting on airs, I guess. One “guitarist,” I forget who, said in a magazine interview that “the days of sitting in your bedroom practicing guitar are over.”

This prideful incompetence didn’t last very long as a punk ethos. Once, in a discussion with the leader of a well-known post-punk band, I mentioned the very first punk ethos that I could remember was not just being young loud and snotty, but unskilled at their instruments. He didn’t know about that, and didn’t seem to know what I meant. Certainly he and his bandmates knew how to play their instruments.

Always well ahead of everyone else in bizarro lore, Ken introduced me to the life and works of Alfred Jarry (1873–1907). Jarry wrote the Ubu plays, Ubu Roi, Ubu Cocu, Ube Enchainee. (King Ubu, Ubu Cuckolded and Ubu Enchained.) This, for me, joined On the Road, Candide and How to Talk Dirty and Influence People as a life-altering work of literature. And I should say that, when you consider what most other people find life-altering—famine, pestilence, civil war, drug war, religion, serial killers–having my life altered by literature makes me fortunate indeed.

Alfred Jarry was a “character” in a time with plenty of them. He was a contemporary of characters like Andre Gide and Oscar Wilde. They found him odd, in fact.

A child from the lower middle class in provincial Breton, he started out on his destiny almost immediately, building puppets and writing stories for them in high school. One such puppet, which started out as a cruel, schoolboy caricature of a hapless professor he had, came to be known as Pere Ubu.

As Jarry grew into manhood, or at least his version of it, this character morphed from a bumbling, provincial educator to the king of an imaginary Poland. Jarry focused on the negative qualities that we all have, pumped his creation full of them, and blew them up into monstrous proportions. Ubu grew into King Ubu, “the personification of all that was evil in mankind.”

Getting a character to convincingly portray all of the (uncountable) negative qualities that humans can have is no small feat, but Jarry was equal to it. He endowed Pere Ubu with cowardice, cruelty, selfishness, dishonesty, homicidal mania and venality, and that was merely a first draft. Ubu eventually became a byword for evil tyrants all over Europe. It wasn’t until decades later that heartier villains like Hitler and Mussolini came upon the scene, leaving Pa Ubu almost cuddly by comparison.

It’s tempting to say that Jarry, with his brain stretched almost beyond endurance by his visions, his genius, his excessive drinking and drugging and his erratic madness, was given a look into the future of the century he was entering. What he saw drove him even madder, and in Pere Ubu, he simply created a personification. Roger Shattuck, his best biographer, described the latter part of his life as “suicide by hallucination.”

Ubu Roi premiered in Paris in 1896. This was a far different world than that of today. There was no drug prohibition. There were no social programs beyond workhouses and private charities and churches. Raw conquests of weaker lands was still seen as an almost noble endeavor. Censorship was in full flower, and was considered an honorable profession. Anthony Comstock, in fact, was still alive. Prostitution was legal, but the use of “impure” language was not. In fact, it was not only illegal, it was an impropriety.

So, naturally, as the enfant terrible to end all terrible enfants, the first word of his play was a variation on Merde.

Merde is the French word for “shit,” and Jarry, to get around the censors, tweaked it to Merdre.

Half of The audience were proper Parisian theatergoers, whose idea of naughty comedies –“Alors! Beware! Mon husband arrive’!”– was a lot different than this. They were thunderstruck. Gobsmacked. Unbelieving. Then their outrage kicked in.

They shrieked. They screamed. They pounded their canes and feet on the floor. They threw things. But then the other half of the audience, mostly from the artistic, bohemian side of the city, jumped up to defend freedom of expression, hooting and howling at the overdressed, bourgeois Philistines.

This led to fistfights, things thrown, walking stick duels. It took a full half hour to calm everyone down. Muttering, they slowly settled back into their seats, dusting themselves off, ready for the second word of the play. Which was, unfortunately, Merdre, once again.

Alors! The audience jumped up and went right back into it, almost eagerly. The French, bless them, take their arts seriously. This sort of thing is almost notorious among French art audiences. There were riots at the 1913 premier of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. I have read that Parisians, outraged at “modernist” tendencies in the work of Paul Cezanne, attacked his paintings with their umbrellas.

Kinda like hockey games, when you think about it.

Alfred Jarry attained notoriety with the Ubu plays, but he didn’t get a lot of money from them. He wrote some books, some poetry, invented the “science” of ‘pataphysics, the science of imaginary solutions. He remained a character about town, a recognized man of letters and a boulevardier, but without the price of a meal in his pocket.

He prefigured—some say helped create—Dada, surrealism and futurism, and received the expected reward from the world around him; he starved to death in a garret.

It was, in fact, possibly the cheapest garret in all of Paris. It had such a low ceiling that even he, under 5 foot tall, couldn’t stand up in it. He would write lying on his stomach. For meals, he would capture sparrows or pigeons and “roast” them over a candle. I am not making this up.

This kind of diet, this kind of life put impossible demands on a body that he thought could be driven by the brain alone. He finally announced that he was writing above everyone’s head, including his own, and that he had to experience death, in order to catch up with himself. He had remained an enfant terrible and was never able to grow out of it, dying at 34.

And yes, I thought he was a great role model.

So, the band my brother and I started was named Ubu. We tried to be as absurd as the name. We did cabaret skits, usually featuring Pa Ubu doing hideous things to the politicians of the day. Dick Nixon, of course, was a great favorite. Then we would play off-the-wall music in between. This eventually moved over to doing skits in between musical presentations. One can only imagine how many gigs we got, even in SF.

We would sometimes joke that the stuff we were doing was so unpopular that it would be our destiny to go pretty much unrewarded. Our lot would be lousy paying gigs and lousier paying day jobs. But, then, once we got old, some bright-eyed young ethnomusicologists would track us down, as though we were blues-singing sharecroppers, and finally get us a recording contract.

Alas. Alack. Alors.

End Jarry Digression

What I liked about free music, and still like about it, was the absence of amplifiers and microphones. I think it was John Cage that said putting music through a microphone is like squeezing a package into an envelope. That made it necessary for the performances to be held in small spaces, which also, of course, meant small audiences, which was pretty much a given.

Anyway, we would bring conventional and newly-minted instruments and pretty much make it up as we went along. This meant a whole lot of ostinados, which were, anyway, all the rage at that time anyway. We were searching for new sound combinations, more than anything else. Rhythm was generally a simple pulse, usually pretty fast.

It would be a lot easier to have included a sound sample of what the music sounded like, but all but one of the recordings have been lost. I even paid for a three-day recording session for all the bands I felt deserved a smidgen of posterity, but the tapes got lost in my many subsequent moves. What I do have is a CD from Moire Pulse, a percussion band led by a wonderful man named Mel Moss. He was a sculptor, out of New York, older than the rest of us. He had gotten bored with merely sculpting things; he wanted to sculpt things that also did things. In this case it was things that sounded good. So he started building slit drums, aka tongue drums, hollow wooden structures with slits on the top. The wood was of a quality that different sized cuts would produce different musical notes. And Mel was such a master with his hands that the drums ended up as works of art.

He couldn’t really play, but he invited musicians to get together and make rhythmic music with his creations. He named the band Moire Pulse. A moire is a graphic, or printing term, that means two lines going in roughly the same direction, following their own path to get to the same point. I was running an alternative music club called Pangaea at the time, booking bands from the surprisingly large pool of players in the free music scene, and I hired his band for an evening. They played, did a very nice job, and I asked if I could drop in at their next rehearsal. I did and I signed up as fourth drummer.

That’s the kind of thing one does, being artistically inclined and under 25. You take whatever day — or night — job that doesn’t tread too hard on your dignity and self-image, and spend the rest of your time working for your art. Charles Ives did the same thing, although on a far higher scale. He was a very successful, almost legendary insurance executive in the daytime and wrote his very unsuccessful, near-freakishly advanced classical music in the evenings. Werner Herzog, in an interview, said that he started as a filmmaker by working in some kind of a factory, saving up enough for the film stock. He made a small film, then went back to the factory to save up enough for the next one.

So they were role models. Since most of us were thoroughly alienated from mainstream society, and the Symbionese Liberation Army was recruiting, it could have been a lot worse.

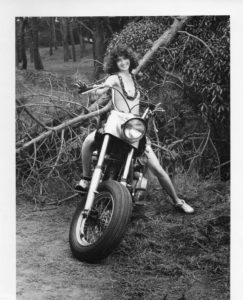

UBU, San Francisco, the 1970s

FROM FREE MUSIC TO SALSA:

After a couple of years of that, I had a serious musical awakening in San Francisco. The very city that got me going with experimental, cosmic, ethereal sounds and grooves provided an escape from it.

I had just played a lousy free music gig at Fort Mason, a semi-military location close to the Marina, and right on the water. It was uninspired, clunky and received in the same spirit. I had some small percussion instruments with me, and decided to walk along the water to get a Geary Avenue bus home.

I was not happy. I had been playing this cutting-edge, bizarre music for about five years and it was getting less and less, rather than more and more, interesting.

After a while I reached Ghirardelli Square, the end station of the cable cars, and actually the end of the continental United States; the end of the square was the beginning of the Pacific Ocean. It had, at any given moment, more tourists than the Vatican.

Coming through the sounds of all these respectable people from everywhere on earth, I heard drums. I heard a lot of drums, and I went sniffing after them.

I found, after five years living and playing music in San Francisco, the drum circle at Aquatic Park. Aquatic Park was a series of tall concrete steps, sloping down a hill that ended at the ocean. Every step was being used as a bench, and guys with congas were sitting on them, playing guaguancos and merengues and sambas. There were guys from the Mission—where I lived, actually—playing Latin grooves. There were guys from the Fillmore, playing “project beats.” There were guys from Africa, playing their folk rhythms on djembes. It was chaotic, of course, with about 50 guys, often drunk or stoned, playing their own rhythms, with only a vague resemblance to what the guy 12 steps away might be playing. It took a long time for a groove to coalesce, but once it did, it became heavenly. I sat down, started playing, and my life changed.

I would spend the rest of my San Francisco days playing, every Sunday, at that park. I would spend the rest of my life looking for similar spots, all over the world. I didn’t find that many, either, until I got to D.C. (More on that later.)

It was in no way idyllic. It had so much street in it that I’m surprised the grooves ever caught at all. And street, in San Francisco, means thugs and loonies. The whackos may have been a semi-amusing minority around the rest of the town, but at the park, with frenzied drum grooves and the general uninhibited quality of just about everything, they were often the defining factor. And they were seldom amusing.

Women were well advised to avoid the area, as a lot of street jerkoffs would, in the words of one of the drummers, “be pimpin’ off us.” This was exactly correct. Any woman that came by would be hit on instantly, sometimes quite aggressively, by some yuck hitting a soda can on the step and pretending to be playing. One jerkoff grabbed a young lady’s arm and wouldn’t let go. She looked to me, obviously scared, and asked if I could help her get her arm back. Well, damsel in distress, you know. Still carrying my timbale sticks, I politely asked the slob to let the young lady have her arm back. After a five minute argument, augmented by some hard stares by another drummer or two, he let her go.

Later, he came up to me. He was drunk, mean drunk, with that evil stare and snarl that alcohol brings to the surface, that cold, unthinking resolution that has helped fill up so many American prisons. “If you ever do that again, motherfucker, I’m gonna kill you.”

I merely nodded. Since this can mean practically anything, I have found this to be a good, neutral way to end this kind of conversation.

I would go on to become a bit of an expert on types of drunkenness, sorry to say, by playing piano in bars all over the world. I got so I could tell when someone was serious about their mayhem or not, and I could tailor my responses. It’s one of those life skills that it would be better not to require, but when you need it, you really need it.

Back at the steps, however, even with the arguing and drunkenness and incipient violence and the drunks that banged on trash can lids, I found something about the grooves so vital that I couldn’t go back to playing in a vague, spaced-out, flowing stream kind of groove anymore, unless there was a fundamental beat somewhere. And with me, it was usually a Latin beat. This, surprisingly, worked fairly well within the “structures” of free music, and I started to think that maybe a lot of the other guys were missing the same thing.

But I had changed my life. I started going to Salsa clubs and soaking up what they were doing. I bought congas and timbales and watched what the other guys were doing. I didn’t actually take too many lessons, but I played with guys who did, and their mastery scared me enough that I would at least practice. It took a while, a lot longer than it should have, but I finally became, well, not bad.

DORI SEDA

I have exactly one published piece from that period, the only one I could find. Most things I lost, and the publications were on the verge of bankruptcy before I even submitted to them. R. Crumb put Bloods in Space in the maiden –unlikely phrase –issue of Weirdo Magazine.

There are a whole lot of oddballs in this world, and only a few spots where they can be themselves without government-mandated electric shock therapy. There were thousands arriving in San Francisco every year from this cultural diaspora. Dori Seda was one of them.

Dori and I started as friends. Tall, thin, perfectly proportioned, she worked as a model and sculptor. After a few years of that, needing a bit of a straight job, she applied for and was hired as a bookeeper for R. Crumb Publications. This is a perfectly legitimate path to fame–Truman Capote started at the New Yorker in the accounting department.

One of us had the idea to collaborate on a comic strip, so I wrote and sketched this one out and showed it to her. She picked up her pen–rapidograph, actually–and did some real drawings, the results of which can be seen elsewhere on this site. She showed it to Mr. Crumb and he bought it.

What I have here is a functioning link to what I just referenced. Through the technical wizardry of Sam Catherman–who, by the way, plays bass in the JazzHop band–one can click on the title and one will be able to read the comic strip:

It was well-received, but we didn’t do an encore. I was getting myself ready for another journey around the world, and Dori went on to become fairly legendary in the world of comics, getting far more attention in that medium than she had with sculpture.

Dori went on to a sort of underground fame as a cartoonist, to the point of launching comic books about her life, until her very premature death at the age of 36.

Years later, In Europe, I made the acquaintance of Lark Ann Cobb, a singer out of Los Angeles. She, it turned out, was a big Dori Seda fan, and promised to give her my regards when she got back, should they ever meet. A year later Lark sent me a note. It contained a clip from the SF Chronicle, with Dori’s obituary. They blamed it on inhaling silicone, from her sculpting, and smoking five packs of cigarettes a day. Later on, I read that her mother, a zealous Midwestern Christian, had practically disowned her and barely accepted the body for burial.

Some time after that, Bruce Sterling, the Sci fi writer, had the bright idea–I don’t say this in an ironic manner, it was a bright idea–to pair her with another underground hero who died young: Lester Bangs, the same Lester Bangs who worked with Richard Walls at CREEM Magazine. The author posited that if they had both lived, they would have met in SF, married and moved to Omaha. The name of the story was Dori Bangs. It ran in Isaac Asimov’s SF monthly.

Years after that, I interviewed for an editorial position at some organization in Washington, D.C. The young lady conducting the interview looked exactly like the Dori Seda of my recollection; thin, cheerful and still 25. I was shaken, to the point where I utterly blew the interview. I kept on staring at her and bringing the subject back to my dear departed friend. She looked so utterly familiar that I put myself on almost intimate terms, smiling way too much and cracking too many jokes. I could feel the young lady mentally filing me away as a creep, but I couldn’t stop. She ended the interview quite abruptly, and I think I saw her shudder.

I like to think Dori would have enjoyed that.

Last Gasp established a Dori Seda Memorial Award for Women, in 1988.

Dori Seda 1983. Photo by Barbara Cotel.

HATING CARS AND GETTING AWAY WITH IT

It was in SF that I realized that I not only didn’t know anything about automobiles, I didn’t like them. Far more to the point, they didn’t like me. Every car I operated would, the minute I bought it, would throw some sort of mechanical temper tantrum as soon as I signed the papers. They were breaking down approximately every two weeks for the entire time I was using them. So my first directed thought against automotive culture came through the wallet.

This released the thought, must I use these fucking things? Which led to a lot of other thoughts. I realized that cars were killing cities, my abode of choice. They were empowering the wealthier urbanites to move to the suburbs, in fact, they actually created the suburbs. Suburbanites are an entire new minority group in this country, if they’re still a minority at all. They have voting and consumer patterns distinct from urban or rural folk. So the cars were transporting those that had been my neighbors into a separate living arrangement, and one that would soon clash with mine. Suburbanites, for example, always vote for things that will aid the automotive culture. Suburbanites have elected venal politicians like Nixon to obnoxious politicians like Rob Ford to unspeakable politicians like Reagan and Trump.

Then, too, the cars were choking and overheating the cities as well. I noticed this acutely in SF; Detroit was practically designed for cars and they were such a part of the natural landscape that I didn’t see anything off about them. But in a smaller, tighter area, filled with pedestrians and cyclists, the cars were like barracuda in a goldfish bowl.

Finally, they gave every person their own individual bubbles. Interaction with your fellow citizens became avoidance, rather than a friendly nod. As we bump one another on foot, a quick apology almost always works. Do that in a car and it calls for a punch in the nose or the lawyers.

I’m not alone in this, of course, but I really felt like I was in those days. And, as always, somebody got there way ahead of me. George F. Kennan, diplomat and intellectual, writing about southern California in the 1950s, talked about the “utter dependence on the costly, uneconomical gadget called the automobile for practically every process of life from birth through shopping, education, work and recreation, even courtship, to the final function of burial. What disturbs me most is man’s abject dependence on this means of transportation and on the complicated processes that make it possible.”

CARS DIGRESSION

Here’s more on the subject; a piece I wrote for the D.C. City Paper, a paper I sold a few pieces to when I first got to town. This one I actually forgot to submit. It was sometime in the early 1990s:

Cars and cities aren’t a good mix. The city constricts the cars, puts them through exasperating parking maneuvers, and forces them to mince around in second gear. The cars retaliate with noise, smoke, filth and certain death for anyone who stands in their way. They cover the city with a noxious cloud, stretch it into an ungovernable size, carry potential taxpayers to homes in suburbs, and lead us into oil wars to slake their thirst. Bernard Rudolphsky, author of Streets for People, contends that they have turned the American streets into the “Entrails of the city. Constipation,” he continues, (is) just one of their chronic ailments.”

Cars have won all of the battles that have been fought over urban primacy, and they guard their turf as jealously as Balkan warlords. There is no social plan or program that you can discuss that excludes the motoring class from the table. Anything that might restrict the free flow of automobiles, even for a couple of minutes, will be voted down. This means that the class whose interest are most inimical to the city is the very one running it.

Me, I would call this tyranny. Or beyond. King George didn’t befoul the air, overheat the summer, turn two-thirds of our cities into a danger zone and demand a sacrifice a 40,000 lives and countless limbs a year. All he wanted was money. And, compared to your neighborhood Ford dealer, not very much of it.

Everyone driving a car is contributing to this, and the price of destroying our cities is not cheap. According to the American Automobile Association, it costs about $10,000 a year to make loud noises, send a trail of deadly smoke all the way up to the ozone and swell the coffers of the Iranian ayatollahs. (Okay, they phrased it differently.) This does not include the cost of the car in the first place.

So I gave up driving in 1975, in San Francisco. I suppose there might have been some latent tree-hugging urge, but the real catalyst was the latest in a long series of exquisitely priced repair bills, each one somehow calculated to leave just enough money to pay for the next one. I was, in effect, working for a car, a machine. I was slaving for a mechanical master; I was living out a science fiction nightmare. Finally–it was more a fit of hysteria than anything else–I drove it into a garage. The garage was run by a lesbian/communist/vegetarian/auto-repair collective, which is, in the Bay Area, just another family business. I left the keys in the ignition and stalked out. I haven’t been inside a garage since.

It was, of course, quite a readjustment, but the rewards were fabulous. Giving up cars means the end of traffic cops, parallel parking, traffic jams and insurance companies. There will be no more snickering pups in garage uniforms, arrogantly adding up costs like a maitre’d on the French Riviera. No more matching metal with your fellow motorists, each one of them protecting their bodywork as though it was their sister’s virginity. No more screaming insults through an open window and then remembering that the other guy is probably packing a gun.

It did mean, however, cycling through San Francisco. The picturesque and charming hills and valleys took on a new meaning. It took me quite a while to figure out how to get my instruments from home to gig to home again. But once I had made the necessary adjustments, the feeling of relief was similar to kicking heroin, which I have also done. And I probably saved about the same amount of money.

End Cars Digression

Hobo Jungle

I still have fond, vivid memories of San Francisco, even though I lived there for a mere 10 years and have only returned once. One evening sticks in my mind.

I had gone to a theatrical production of The Threepenny Opera. The Threepenny Opera–Die Dreigroschen Oper–was a signature theatrical piece by Bert Brecht and Kurt Weill which became a signature for the lost art of the Weimar Republic. Weimar was destroyed by the Nazis and will forever be associated with Hitler and Goebbells and Goering, just as Sharon Tate will be forever linked to Charlie Manson. So, 50 years later, there was still a current of tension present in anything that evoked those times.

When I walked in, there was an unpleasant smell in the place, reminiscent of rotten eggs, which is in itself reminiscent of crowd control tear gas. Had the cops raided the place? I thought it might be possible; there was a lot of hatred between the SF lefties and the SF cops. So I sniffed the air and asked, in a general audience kind of question, “What’s with the tear gas?”

One guy piped up. “They were looking for Marinus van der Lubbe.” I thought that that was pretty funny, and damn quick. Marinus van der Lubbe was the simple-minded Dutch communist that the Nazis blamed–and beheaded–for starting the Reichstag fire. But then almost everyone else in the room laughed as well. They had all, apparently, read enough history to know the poor guy’s name, and to understand why cops would be chasing him.

The play began. In between each scene someone would bring out a poster saying things like, “Every minute on this planet, 48 children die of malnutrition” or “America has more hungry children than Bangladesh. Think about it.” This went on throughout the entire production. And when the play was over and we all set off for the pubs, someone hollered out, “Well, time to get something to eat.”

Everybody laughed at that one, too. I thought, these are really my kind of people.

But even with all the odd things that still go on there, with its high percentage of America’s fringe dwellers, the most interesting story out of that decade came while I was out of town.

It was somewhere in the middle of the 70s when I got the idea to visit New Orleans for the Mardi Gras. I answered a ride share ad and set off with two other guys in an automobile, my first auto journey anywhere in a year or two. This was before I had fully realized the ill effects that my mere presence has on machinery. It wasn’t just cars that I found contrary and incomprehensible, it was anything mechanical at all. I think that I project some sort of ionic disruption field, one that only mechanical devices can appreciate. It apparently saddens them, producing the same effect that tragic news does on humans, and they can’t really function.

It took me half my life to realize how truly lethal I am to the mechanical world. Even if I follow, precisely, the instructions on anything, it won’t work, or if it does it will come apart at the first hard jab. Merle Miller once wrote, after being unfavorably compared to the neighborhood Good Boy, who could “fix anything,” that “I can break anything.”

What happened in this case was, one of the guys was talking about a tape of Mexican music that he had, and he made it sound so interesting that I asked him to play it. He said it was in the trunk of the car, and didn’t want to bother getting it out just yet. I, in my zeal and still ignorant of my psychic destructo-powers, asked the driver to stop and get it out. We were on a 2,000 mile journey, what was four minutes to get some music?

He shrugged, stopped the car, got the tape, put it in, and re-started the engine. Which, of course, didn’t start. Nor did it start at any time in the next half hour. I can only presume that there was a problem with the carburetor. And it never did start as long as I was anywhere near it. And as far as I know, the car is still there, rusty with time, with an old greybeard inside, grimly turning the key ever few minutes, cursing in-car stereos, carburetors, taped music, and of course, me.

So this was a sinking ship worth deserting, and I did so, and stuck out my thumb. This was right up to the edge of the last days of hitchhiking, which pretty well came a cropper in the mid-80s. Truck drivers had a host of new insurance regulations forced upon them, and news of hitchhiker killers and mad-dog hitchhikers was getting a wider distribution. Freeways–the true hitchhiker killers–were taking over the landscape. I hadn’t quite gotten this yet; I hadn’t hitched in a couple of years and my life coach on such matters was still Jack Kerouac.

It started out surprisingly. I had been on the highway for 25 minutes and a woman picked me up. She was reasonably pretty, in a suburban housewife sort of way, with soft brown hair and a sly smile that was quite endearing. If I wondered why she had picked up a hitchhiker in the middle of the night, I soon found out. After about two minutes of pleasantries she invited me back to her house have sex with her, while her husband watched and cheered us on.

Well, even after five years in pre-AIDS San Francisco, I couldn’t believe it. This is the sort of plot twist that you couldn’t get past a porn-book editor. It was too obvious, too unbelievable, and too insulting to the intelligence of your average porn-book readers. But it actually happened to me, and, if this woman was to be believed, it was something she did about once every couple of weeks. “After I put the kids to bed, I thought I’d take a look and see what was on the highway.” You may believe this or you may not believe this, but bear in mind that this was California during the–er–swinging 1970s.

Well, it had to beat standing on an off-ramp, covered in exhaust fumes and the middle fingers of a whole lot of pickup truck drivers, so I said sure. We got to the front of her house, but she stopped short of the driveway. A certain light was on, which turned out to be a signal from her husband that it was not okay to bring in any Highway Studs. Either the kids were awake or one of the neighbors had dropped in, and if she had any hulking sex brutes in the car–that would be me–it was time to cut them loose. So she turned around, apologized, and dropped me off back at the same spot. I curled up under an overpass and went to sleep, dreaming of The Stepford Wives, naked.

For reasons that are instantly familiar to all hitchhikers , I ended up nowhere near New Orleans. One just follows the flow of the rides one gets and hopes for the best. A couple of rides later I found myself on the highway outside Indio, California. This was a revelation, kind of. A year or two before that I had been introduced to the music of Harry Partch.

Harry Partch was a composer and inventor of bizarre musical instruments, like the cloud chamber. He took items that had been tooled for a specific, usually industrial use and found ways to make music on them. He utilized a tuning scale called Just Intonation, which is a mathematical system of musical tuning that brings the frequencies of the notes in line with small whole numbers. And the fact that I can toss off a sentence like that doesn’t mean that I really understand it, or could tune anything Justly. But Harry could, and more power to him.

Harry spent most of the Depression as a hobo, filling a journal with insights and poetry, working when he could. He hit what was for him The Big Time after WWII.

I remember one poem he set to music, something about “Indio, California, 1938. Don’t get caught by the cops, they’ll put you on the road gang…”

And, suddenly, there I was, on the highway, just outside Indio, California, 40 years later. The hitchhiking was dreadful; it was in fact some of the worst I’d ever done in my life. Every fourth driver gave me the finger or yelled out something like “Getta job, stinkin’ beatnik!” These people were quite possibly the direct descendants of the ill-tempered sodbusters that gave Harry such a rough time. Carrying on the local traditions, you might say.

After two hours, I said the hell with it, and walked down into a valley that seemed to lead into town and the Greyhound station. But instead of that, I stumbled upon a clearing with a campfire, laundry hanging from trees, railroad tracks, and six or seven people sitting around, cooking cans of beans over the fire! A classic hobo camp, with real, live hoboes! Egad. This was practically a lithograph coming to life. One of many unbidden thoughts that raced into my head was, Golly, wait till the folks back home see this. (Fortunately for all, it was well before the age of selfies…)

I approached them, smiling, suddenly acutely conscious of my leather jacket and un-stained clothes, expensive traveling bag, and high tooth count. I felt like a wayward rich kid, coming to bestow a copper or two and snap a few shots of the vagabond class. Actually, I expected to get robbed. But the same sort of idiot curiosity that sent me to the Bombay-Mombassa passenger ship pushed me forward.*

*The service, notorious for accidents and sinkings, was discontinued a year before I got there.

Everyone was polite and friendly, however. They told me that they were waiting for the right kind of train to hop. One guy said that he’d been riding the rods for five years, and was about halfway through his “apprenticeship,” meaning that he was learning how to translate the scrawls and marks on the rear of a car into its true destination. “You don’t wanna wake up and find yourself stuck in Montana,” he said, more than once.

I remember reading Carl Sandburg’s autobiographical On the Road when I was in high school. Apparently Mr. Sandburg rode the rods during the Panic of 1897, avoided getting crushed beneath the wheels and the hundred-odd other mortal dangers of that kind of life, and lived to tell the tale. And he told it well. That, along with Kerouac, and the pre-war memoirs of a German hobo, Notes of a Vagabond, had really affected my thinking and outlook for years and years, and there was still enough of that stuff left in my brain to legitimize this sort of life.

Well, my joining this crew didn’t extend to their offer to share a plate of beans. I figured that they needed nourishment far more than I did, and this was probably all they had. But I was drawn aside by the only woman in the group. She gave me a beckoning smile, but I was having none of it. Getting cozy with the hobo chieftain’s girl–which she must have been, and if she wasn’t, she soon would be–was not something I was gonna even think about.

I thought she was going to suggest that we travel together, in luxurious Greyhound comfort, paid for by me, and start a true adventure together, also paid for by me, and finally toss me aside after stealing my clothes and luggage, also paid for by me. But no, she wanted advice. She had come across a driver’s license, photo ID, of a young lady from San Diego. According to the license, the young lady was 19 years old, beautiful in a pampered, surfer-girl kinda way, with the kind of big, innocent smile that we associate with McDonald’s commercials. She looked like she should have been dating the captain of the football team on Leave it to Beaver. The woman at the camp, who looked about 30, with one of her front teeth missing and a knife scar under one eye, wanted my opinion on whether she looked enough like the cheerleader to pass some bum checks in L.A.

“Well….” I said.

“‘Cause look. She’s blonde and I’m blonde. Ya know?”

“Well, yeah…..” She was, it was true, blonde, the dark, stringy, unwashed variety. She was blonde for whom the phrase “Dirty Blonde” had been coined. So, she was technically a blonde….

“And I can talk fancy, like this bitch. So whaddaya think?”

“Well, I dunno.” I dug desperately in my mind for an answer that wouldn’t hurt her feelings or encourage her to attempt this waxed glide into a cellblock. Basically, she gave off the unmistakable aura of the street, or the hobo jungle. Or the doss house. Or the reformatory. Or actually all of them. Sending her into a Nieman-Marcus posing as an upper-class prom queen would be like casting Hulk Hogan as Truman Capote.

I was to wait decades to see her type brought to the screen, brilliantly, by Charlize Theron in Monster.

All I could come up with was, “Well, gee, I’ve never worked in a bank or a store, ya know? I don’t know how they judge people. Ya know?”

She sighed. “You’re supposed to know stuff like that. These other guys don’t. I mean, you’re from out there, ya know?” She spoke of the functioning world as though it was another dimension.

I didn’t know what to say to that. In fact, that type of gangsta’ pathos kind of broke my heart. All I could do was apologize and take myself back to the campfire.

The guys there asked me about my own plans, and I told them I was trying to hitchhike to Nawlins. They were shocked.

“You wanna hitchhike, around Indio?” one guy asked, as though it was a plan to bugger a musk ox in the town square.

“Don’t fuck around like that here,” he said. “Don’t get caught by the cops. I mean it. They’ll put you on the road gang.”

It took a minute to put that together, but it finally hit. This guy, although he certainly didn’t know it, was quoting the Depression-era ballad from Harry Partch. I had fallen into a Harry Partch song. I was living in a Harry Partch song. I sat back for a long moment, rather stunned. I’m sure people have found themselves living in a lot of songs, but they’re usually songs about cheatin’ spouses or unattainable love or even brands of cars. But I had stumbled into a song that almost no one in the world had heard. And it was coming true.

“Well, I said. “Talk about consistency. Talk about art imitating life imitating art. This shows the kind of social progress made by the good citizens of Indio. And riding the rods in general.”

“Huh?” they asked.

I’d like to end this little tale with a Hobo poem, from 1914:

Bread

Oh, my heart it is just achin’

For a little bit of bacon

A hunk of bread, a little mug of brew

I’m tired of seein’ scenery

Just lead me to a beanery

Where there’s something more than only air to chew

Henry Herbert Knibbs

Songs of the Outlands: Ballads of the Hoboes & Other Verse

Houghton, Mifflin 1914

MEXICAN DIGRESSION

I took a Greyhound out of Indio, stuck my thumb back out in Arizona, and suddenly realized that New Orleans was still a thousand miles away, through places like Texas, while Mexico was practically a taxi ride away. I caught a ride to Nogales, and walked across the border.

I liked Mexico from the start, and I was quite well treated there. I took a train to a harbor town called Guyanos and booked a room in an old-fashioned hotel overlooking the main plaza. There was some sort of a festival that night, with Mariachi bands playing at 50-yard intervals. And after a joint and a couple of tequilas, in the climate where it was nurtured, mariachi music started to make sense. Up in San Francisco I would run screaming from it, but there, with an ocean breeze and dancing girls, it somehow didn’t sound that god-awful.

I did some more hitchhiking in Mexico, just to see what it would be like. I went from Puerto Vallarta to a fishing village named, I think, Bucerias. I went into the town pub, and met some local guys. They were fishermen, and for some reason they invited me to join their fishing crew, starting the next morning. There was no pay, but I could get my pick of the catch, and the pub, which jutted out straight out into the water, would clean and cook it, and serve it up with rice and beans. Three times a day, if I wanted. I would also be given a rowboat to sleep under, on the beach. I thought, what a lark that would be. I didn’t know how closely this would parallel the job conditions for college graduates in the 21st century.

I accepted, and it was wonderful. The craft of fishing there was pretty simple. Some guys in a boat would go out about a mile and lay down a huge net. Then, we–the ground crew–would walk out to the net–the water never came above my waist–and pull the net in, capturing hundreds of small to medium-sized fish in the process. We did this twice a day and that was it. Then we would take our share of the catch to a waterfront restaurant and let them turn it into dinner. I like to think that the rest of the crew got paid something for this sort of backbreaking labor, but I was perfectly content.

One guy introduced me to his cousin, a comely lass of about 18 or so. And not for sex. They had bigger plans. They figured that after a couple of weeks of this beachcomber idyll my Yankee work ethic would kick in and I would return to El Norte and reclaim my spot on the stock exchange. And maybe young Inez could come along. If we couldn’t marry–my social position, the scandal, dontchew know?–then maybe she could keep house and boss the servants around. It was certainly worth a try.

Indeed, who knows about these things? I have to say that I merely suspected that this was the case, but I was in no mood to settle down with anyone.

My Yankee work ethic did kick in, and I left the village after a week or so. But every time, since then, that I wandered into a fishing village somewhere….

End Mexico Digression

Jail Dudes

I’ve been jailed in several cities, in the U.S. and overseas. It was always for dope. Thanks to shitballs like Harry Anslinger, Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan, and the ill-informed hysteria of American voters, millions of otherwise law-abiding citizens can say the same.

The only jailhouse story I will share is that once, the entire band I was playing in got arrested, en masse, in San Francisco. For marijuana. When you get past the fact that this country criminalized a flower, wasted billions of dollars of public funds and ruined probably millions of lives in the process, the circumstances were kinda funny. At least in retrospect.

We had a guitarist who was transitioning from a man to a woman, and about halfway through that she took up with one of the street guys in Potrero Hill, where our clubhouse/performance space Pangaea was located. She was a fine guitarist, but she had grown up in the country, and during her life as a man her day jobs included rough work with bulls and hogs, which gave her an impressive set of muscles. What she didn’t have were any sort of street smarts. She had no idea, for instance, that this rough-trade dude might have been under a couple of warrants, and would gladly shop her and her band to get a sentence reduction. Which is pretty much what happened. In yet another waste of taxpayer’s money, we were all collectively busted for our guitarist’s arranging a sale of an ounce of weed to this dipshit.

Once booked and assigned a cell, my cellmate–called “cellie” in these times–a real-life stoner cliche straight out of Cheech & Chong, said, “Wow. Far out. A whole band. Far-fucking out. So, how much weed didja bring, man?”

“Actually,” I replied, “not having any more weed is usually one of the first things that happens when you get busted for it.” I have to admit it took me a minute or two to form that reply, but I felt it was worth it.

He didn’t. He wasn’t having any of that. That was the square-ass kinda logic he heard from his public defender. All he knew was that this was a seven-piece band and none of them had any reefer to smoke. What the fuck kinda band was that, anyway?

“Well,” I said, “we utilize dissonance and atonalites and the mood of the moment to produce–”

“Never fuckin’ mind,” he snarled. Then he took his case to the public. Banging on the bars, he yelled “Whole fuckin’ band gets popped and they dint think to stash any weed for us! They let the fuckin’ cops take all their weed!” He made that point several times, to the entire floor, even to the guards.

Other than that, though, he was all right. I slept soundly, unbothered, and made OR (own recognizance) a day or two later. And since the country—and especially San Francisco–was starting to treat marijuana “offenses” a bit less idiotically, I had to attend a weekly drug rehab class for a couple of months and that was that. This was a couple of years before Reagan sent it all back to the style of Calvin’s Geneva.

THE END OF THE AFFAIR

Finally, though, at the end of the decade, I had had enough of San Francisco. It was too groovy, basically. Everyone praised each other’s art forms, no matter how awful they were. Political Correctness was being born, and catching on. I gave the practitioners the term “Arch-liberals,” which didn’t catch on. There wasn’t much functioning criticism, so most of the stuff stayed at the inception level. Or that’s how I felt. There were great players, many far better than I. But I wasn’t sure what I was doing was good or just fun.

A saxophonist and San Francisco native, Lisa R–, had the good fortune to meet Art Blakey while he was touring. He told her that one had to go to New York if one wanted to get serious about playing jazz. This is pretty much what people told Leo Wright when he was in the same city, 20 years earlier. I don’t remember where she went, but she did leave town. And she’s still playing.

I remember a story about the Cockettes, a dance troupe of cross-dressers, who described themselves as “chicks with cocks,” who had taken SF by a bit of a storm. It was the height of outrageousness–I went to one of their shows called Journey to the Center of Uranus–and it was simply ridiculous. Laugh Out Loud ridiculous. They were the perfect backup group for someone like Divine, and indeed, she joined them for that very purpose for a while. But in their New York debut, they were nervous and disorganized. Nurtured in San Francisco, however, they thought that their messiness was somehow cute and added to their appeal. And–and this is my point–nobody was gonna tell them otherwise.

So they bombed in New York. Gore Vidal, walking out, was heard to mutter, “Merely having no talent is not enough.”

In the fall of 1978, Jim Jones killed his flock in Guyana. I had been in the People’s Temple, once, to talk about playing there. I don’t remember who I spoke with–it wasn’t Jones–but I do remember thinking that this place was even more disorganized than the free music scene, and I never went back. Then, about two weeks after Jonestown, a pathetic right-wing shithead murdered City Councilman Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone. The shooter—to quote H.G. Wells, writing about some equally odious 18th century shithead—“I will not burden the reader with his name”–became immortal for his “Twinkie defense.” His lawyer said that he hadn’t eaten anything but Hostess Twinkies for days, and blamed an excess of blood sugar for sending him off the deep end. Yeah, right, and was that the mayor’s fault?

It was a very stupid defense, aimed at sympathetic right-wingers, so naturally, it worked. It has now entered the legal lexicon: “Slang for a claim by criminal defendants that at the time of the crime, they were suffering from a mental impairment (short of insanity) caused by intoxication, disease, or trauma, which prevented them from having the mental state required to hold them responsible for the crime. ” Diminished capacity. Leave it to San Francisco to discover the most finite slivers of mental illness and then grade them.

When the shithead got four years, there was a riot. I had a friend that did five years for selling marijuana, and I wasn’t the only one. Right-wing crime is almost always treated more leniently than that of the left, in any country at all. This was starting to look like justice you’d get in Wiemar Germany, not Baghdad by the Bay.

I was gone well before the riot, missing yet another piece of news. In January of 1979, I left the country, traveling by public transport, trains and buses, through about half of Asia.

My leaving had nothing to do with the murders or Jonestown, I was simply tired of working in the arts for no money. I was tired of the arts themselves, and I was especially tired of artists, rolling in to the gig an hour late and explaining that they’d been abducted by aliens again. Beyond that, I was tired of people. Sartre once wrote that “Hell is other people,” and that’s just how I felt. So I sold my gear, cashed in my savings, and got on a flight to Hong Kong.

Comments

Leave a Reply

*

Be the first to comment.